All about the game of resources and identities, understanding intersectionality with respect to the reserves of Uttarakhand and the politics around it

“Hey, hello, you, who are you? What are you doing here?” A forest guard asked me when I was going around for some interviews. Areef and Ahmad were next to me and asked me to stay confident. They leaned forward and said she is with us, her name is Salma, she is from Gendikatta.

This happened last December, in Rajaji National Park when I was working on documentation of Gojri Music for Living Lightly. The community stays within the reserve forest and is fighting for land rights. As the migrating community used to go to the upper meadows during summers, they were not able to show the three generations living in the same place and hence it is difficult to claim the right on the land. There is no policy around migrating pastoralists and keeping these things in mind, now people have started living here permanently to show their existence on paper.

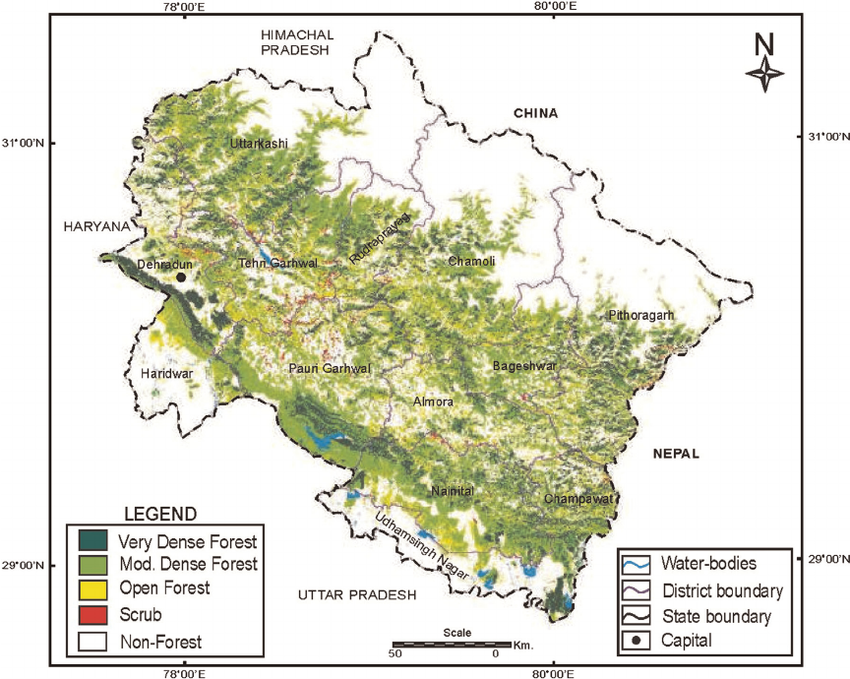

Uttarakhand altogether has 45.44% of forest cover according to the Forest Survey of India 2019 edition. Thousands of people from Tarai, Shivalik and lower Himalayan regions depend on forest resources for livelihoods and sustenance. Yet it is amongst the worst performing states when it comes to forest rights act.

Three major stakeholders who are directly or indirectly involved in decision making which affects the forests most are discussed below. Their role, responsibility and relation with the forest are quite different.

State – The Ultimate “Heir”

The forest department was formed in 1864 by the British and back then was called, Imperial Forest Department. With changing times the state came up with acts and regulations to control the use of forest resources. The age-old colonial structure looks after protected, reserve and unclassified forests. It undertakes full responsibilities regarding conservation and upgradation of ecological biodiversity of the forest. The language on paper makes it sounds like the state acts as the mother of the forest who will keep the child first no matter what. The conservation act, forests rights act, rise and fall of Van Panchayats are some of the examples of how the state planned to take care of the forest. All of these mention the sound argument of instructions to use forest resources. But the structure lacks authenticity.

On the ground, while crossing the reserves one can see plantations sites, electrified fences to keep animals away from roads and villages, huge patches sanctioned for industries, defense practice lands and of course the road we will be crossing by. Many pressures play their role to end up in this scenario and this is not a complaint letter.

Scientists – The Torchbearer

Behind every Akbar, there is Birbal – a wise advisor to the policy maker to consider his steps and account for it. The ecology scientists, academicians, researchers and conservators bring data to the table. Quantitative, qualitative and analytical, they choose which aspect to bring under the light and even more critical, how to present it.

Areas such as discovery of new species, understanding new food chains, exploring behavioural patterns amongst the lesser known breeds, changes in flora fauna throughout the timeline, major challenges faced by the ecosystems, new problems such as climate change and their effects on forests and so much more is explained to the world by the academic sector, in a way it opens our minds to understand what happens inside these vast oceans of wilderness. This results in widening our spectrum of knowledge of what the forest looks like. While all this looks great, it’s important to take into account how it is affecting the forest.

Output of these studies can also be papers that talk about conservation of one specific species or endangered breed and activities related to it. The process of isolating these species and lack of understanding the codependency leads to development of either temporally applicable or unfair policies and regulations.

Ecology changes from region to region and so does the quantity and quality of day to day forest – humans interactions. So the process of maintaining the forests has to be along with the participation of all the stakeholders involved and the academic sector does not necessarily account for the social aspect of forest. This can lead to social conflicts and that gap in communication affects forests. This paper published by Atree (Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and Environment) talks about this separation in more detail. I would specifically like to say that this is not to target a paper or institute. Rather, it is a generalized understanding of publications out there and policies made by considering them.

Community – The Keeper

Ironically the forest keepers don’t have much authority over the greens. Yet, they are the ones who are majorly responsible for direct exchanges. With or without a base of traditional or indigenous knowledge the grassroots continue to interact with the forest. Their relationship with the forest is definitely longer than from 1864. Common resources look like timber, water, berries/fruits/veggies, grasses, leaves, and soil. In some cases, meat in exchange of dung, water puddles, seeds dispersal, even contribution in biodiversity conservation and to stop forest fires. These exchanges can sometimes be uneven resulting in loss of ecology. It is eventually going to affect the locals more than anyone else.

Even though the development sector is working closely with the grassroots for awareness and sustainable livelihood support, its scale and power is limited.

Humans are just another species on this planet who are responsible for challenges such as global warming, resulting climate change, deforestation and a lot more. Imagine a mother with 100 kids, one of which is choking almost 99 others.

Forests cover 31% of the global land area. Approximately half the forest area is relatively intact, and more than one-third is primary forest (i.e. naturally regenerated forests of native species, where there are no visible indications of human activities and the ecological processes are not significantly disturbed).

– State of world’s forest 2020, food and agriculture organization of United Nations

Even if we realize our mistakes and work towards a better future, it still will not bring back all the lost species. Our internal wars over protecting, reserving or owning a piece of earth is benefiting no one, not even us. Eventually the mother is going to answer, either this way or that, so let us be a wise kid and look at the problems instead of owning them.

0 Comments