The Maheshwari weaving cluster, known for its exquisite handloom saris, has undergone significant economic transformations over the years. This collection of essays explores the economic dynamics of the cluster. Changes in design, materials, working conditions, and organizational structures have shaped its evolution over the years. From streamlining designs to embracing modern tools, the Maheshwari weaving community has adapted to challenges while preserving its heritage.

Understanding The Evolution Of The Maheshwari Saree: Going Down The Memory Lane With Mulchand Shravnekar

Opening the doors to understanding crafts can take one through a deep dive across ecology, culture, tradition, materials, and techniques. The identity of any craft finds itself in the overlaps of these factors: the local ecology and material, and the techniques, processes, and tools used. Additionally, it lies in the communities that are involved – both the producers and the consumers. All of these factors have shaped any craft that we see today.

One of the notable changes in the Maheshwari weaving tradition is the shift in design. Traditionally, the heavy pallu sarees with intricate motifs covering the body have given way to simpler designs. The contemporary Maheshwari sarees focus on clear borders inspired by traditional elements like Lehrer and Shakar. The heavy pallu, big booties, and chequered patterns have faded. This makes room for more modern, formal designs suitable for diverse occasions, including office wear.

The material transformation is equally significant. Earlier, the yarn underwent a sizing process, involving the addition of starch before setting it up on the loom. This tedious process has been replaced by the use of mercerized cotton, eliminating the need for sizing. Additionally, the introduction of a mechanized process, involving a variety of diameters in a whopping machine, has streamlined the pre-processing of the yarn. The modernization of looms has made them more portable and efficient, reducing the space requirements for their setup.

Various organizations hoping to promote a fair value chain for this craft have further contributed to the transformation by focusing on contemporary designs in thick cotton, aligning with modern market preferences. The Maheshwari saree has successfully adapted to the changing market demands, striking a balance between tradition and contemporary appeal.

Migrating To Maheshwar: What Started With Migration Will End With Migration?

Associated with most crafts is a specific producer community. The Wadha Suthars of Kutch working with lacquer, the Kumbhars working with pottery and the Meghwals working with weaving. The identity of both the craft and the craftspeople are informed by one another, which makes the craft indigenous to the place where the craftspeople belong.

Weaving in Maheshwar however, shows us a different story. The Maheshwari weaving cluster has for a very long time employed people from diverse social backgrounds. It is not just the traditional weaving communities that weave. And Not all traditional weaving communities are indigenous to Maheshwar. Under the common label of “Maheshwari”, you will see hints of Maratha, Malwa as well as Sindh. Shyam Ranjan Sengupta explains,”

“The Ansari, Maaru, Saalvi, Kholi and Khangar communities were the traditional weaving communities that had migrated from different parts of India to Maheshwar during Ahilya bai Holkar’s reign”.

Sengupta has been working as a manager with the Sant Ravidas MP Hastashilp evam Hastakargha vikas nigam for the last 30 years in Maheshwar.

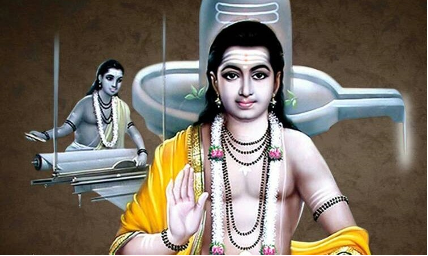

This was the first of the many migrations that set into motion the evolution of the weaving practices in Maheshwar. The Maaru community, originally from Baluchistan, is said to have traveled via Sindh to Gujarat and Rajasthan, before they made their way to the heartland of India to train the local artisans to sustain the state’s economy. The Saalvi community on the other hand worships Lord Jivheshwar, depicted as a weaving god. Saalvis, though found all over India today, have strong roots in parts of Maharashtra. These weaving communities brought with them their expertise and craftsmanship that blended with local traditions of gift giving in the royal court, to give rise to the iconic Maheshwari sarees.

“Maheshwar saw the influx of weavers from Sausar, Madhya Pradesh between 2000 to 2003”

Sengupta cites the failure of the well intentioned but short sighted Janata Dhoti Scheme launched by the Government as one of the reasons for migration. He also recollects how the weavers started taking looms and orders back to their hometowns. The communities in Maheshwar got together and took action against this which led to a lot of the weavers migrating back. Most of the weavers from Sausar are said to have migrated back, however some happened to settle down in Maheshwar and are now commonly known as the Nagpuris.

The economic prospects have prompted several indigenous communities like the Kewats and Kahaars to take up weaving. Handloom as a cottage industry is well synergized with agrarian lifestyle. The handloom provides employment for at least 280 days, where the aggregate income ranges from 175 – 300 rupees a day. This blends with agriculture which provides 60-90 days of employment in two seasons, and where the aggregate income is about 75 rupees a day. The combination of the two occupations are complimentary, prevents urban migration, and allows multiple income generation for rural households. (States Sally Holkar in an interview – click here)

Usha Dhakate’s Case

Usha Dhakate, one of the weaving trainers at Kala Maitri migrated to Maheshwar with her husband, in 2012. This was after her brother-in-law insisted on the booming scope of weaving in Maheshwar. Even though both Usha and her husband come from families that have practiced weaving Kosa silk in Baloda, a town in the Janjgir Chanpa district of Chattisgarh, she learned how to weave only after coming to Maheshwar. She explains,

“Baarish mai Kosa sookhta nahi hai, isliye dhandha down rehta hai. Yahan to saal bhar dhanda chalta hai”

As one of the reasons why moving to Maheshwar has proved to be beneficial. Back in Chhattisgarh, the seths (master weavers) would provide them with silk pods. They had to be boiled and turned into yarn by rolling it on the thigh. It’s a fairly labor-intensive practice that paid them Rs 3000 for every 35m of yardage. On the other hand, weaving a 6-meter Maheshwari Saree that pays them at least Rs 800.

Her husband also shares that he had quit weaving when they got married because of the limited prospects in weaving. Weavers and master weavers struggled due to the lack of market linkages and high cost of investment. In Maheshwar, the investment for purchasing all inputs is made by the master weaver and it is responsible for selling the output. This has taken the risk away from the weavers and is possibly the primary reason for the return of many a weaver back to their traditional livelihood.

The “Lucknowis”

Even today Maheshwar has upheld its reputation for handloom saree weaving, attracting an influx of migrants seeking sustainable livelihoods. Between 2012 and 2015, more than 200 weavers migrated to Maheshwar, drawn by the expanding opportunities within its handloom enterprises. These migrant weavers, often referred to as “Lucknowis,” are skilled and efficient workers, having migrated to Maheshwar from parts of Uttar Pradesh seeking better opportunities.

The Maheshwari weaving cluster becomes a hub for them, offering not just work but also a supportive living environment. While the better wage rates and less intensive weaving techniques act as major pull factors for migration to Maheshwar, the master weavers create an enabling ecosystem for the weavers to settle down in this town. They not only provide the weavers with work but also accommodation along with the loom that they work on. This works out well for migrating families where both the man and wife are weavers.

What Does Rabia Think?

It is hard to estimate the exact number of weavers that have migrated to Maheshwar as the last census was conducted in 2011. There is also no data on the effect of Covid on these migrations. It is evident from the mushrooming construction of brickwalled houses with temporary roofs in the Mominpura (large muslim population) area that the influx is still continuing.

If you were to peep inside from the door of one of these concrete huts you would see Rabia sitting on the loom next to the door, her hands and feet moving to the rhythm of the pedals below her feet as her eyes dart from one end to the other following the shuttle. On asking for how long she has been weaving she tells me that she learned to weave from her mother back in Lucknow as a young girl and has been weaving ever since. She lives with her husband who is also a weaver and her four children. They moved to Maheshwar couple of years back in search of work. She also tells a tale similar to Usha.

“We wove stoles and scarves back home. I earned 20Rs for a stole back in Barabanki whereas here I get 80Rs per meter that I weave. It’s a necessity for both me and my husband to work in order to raise our children.”

Rabia and her husband together are able to weave worth Rs900 daily as they each weave one sari a day. The get paid on weekly based on the number of sarees they produce. The room in which they stay, the loom as well as the raw material is owned and financed by the Seth that they work for. Their only expense being the rent of Rs1800 per month apart from their living cost.

The houses that the Lucknowi weavers stay in stand in huge contrast to the ones in the weavers colony that were once provided to the weavers to promote weaving. Sally Holkar’s efforts in reviving handloom weaving in Maheshwar led to the establishment of the Rewa Society and Women’s Weave, creating a weavers’ colony with amenities such as houses, schools and clinics. This initiative aimed to provide weavers with a conducive environment for focused weaving. Rabia has never made it up the hill to see any of it.

Women Weavers Turn Entrepreneurs: Mamta’s Story

In most parts of India, barring the north east, the skill of weaving remains largely in the hands of men. One of the main reasons for the success of handloom weaving in Maheshwar has been shifting weaving from men to women and repositioning the men in other ways that link them to the craft.

Prior to the coming of Rehwa Society, it was the men who were the weavers, while the women played subsidiary roles by performing ancillary work such as spinning, assisting in dyeing. Rewha as a localized movement began by training 12 young women from nontraditional families. In 2002 Sally Holkar expanded the movement initiated by the Rehwa society into a larger and more ambitious independent, organizational network called the Women’sWeave.

With the rising number of women weavers the cluster also saw men choosing to be engaged in activities connected with the outside world such as marketing, acquiring raw material etc. A better understanding of the market led to an increase in social capital that prompted a lot of weavers to set up their own firms and become master weavers.

Ever since the revival of weaving in Maheshwar supported by the Holkars, the cluster has gained multiple enablers of enterprise. With multiple organizations implementing initiatives for market linkages and training in social media along with the government providing access to capital through the Mudra Loan Scheme, it seems like a ripe space for weaver entrepreneurs to emerge. Mamta happens to be one such enterprising individual who has come a long way.

In the heart of a small town, where the rhythmic clatter of looms once faded into the background, a remarkable story unfolds — the story of Mamta, a master weaver and entrepreneur who transformed her mother’s legacy into a thriving enterprise. What sets her apart is not just her skill at the loom but her visionary spirit that weaves dreams for an entire community.

Her mother, having learned the art of warping at Rehwa Society, set up her own warping machine, servicing smaller clients and nurturing a dream to establish a weaving karkhana for women. Unfortunately, she passed away, leaving Mamta with an unexpected responsibility. Fuelled by her mother’s aspiration, Mamta underwent extensive weaving training at The Handloom School just before the pandemic, forging connections and laying the groundwork for her entrepreneurial journey.

She started by reopening the three looms that once belonged to her mother, reviving the legacy one thread at a time. Mamta’s strategic thinking came to the forefront when she associated herself with the NGO, Karghewale, securing orders and ensuring a steady flow of work. Recognizing the importance of diversification, she tapped into her entrepreneurial spirit by sourcing orders from a Maheshwari saree shop owner who also happened to be a master weaver. This move showcased her ability to navigate the weaving business with finesse and creativity.

Understanding the risks of dependency on a single party, Mamta keeps a watchful eye on her weavers, fostering a sense of unity and cohesion within her team. Her keen understanding of her weavers’ skill sets enables her to allocate work effectively, ensuring each artisan contributes their best to the collective tapestry. Guided by a clear vision, Mamta not only oversees the intricacies of weaving but also mentors her team, correcting mistakes and encouraging continuous improvement. She believes in pushing the boundaries of complexity, recognizing that once a weaver becomes accustomed to intricate work, the allure of basic sarees fades away.

In the looms of Mamta’s enterprise, threads intertwine not just to create beautiful sarees but to weave a story of resilience, creativity, and empowerment. Mamta stands as a testament to the transformative power of passion and skill, leaving an indelible mark on the world of weaving.

Even though there is a larger number of women weavers than there was two decades ago, you will find only a handful of the likes of Mamta. The women might have become earners in their households but the decisions related to enterprise still largely stay in the hands of the men. Especially because they have taken up all the market and coordination related responsibilities. Women who have been weaving for a decade still depend on men for processes like jodni, reed filling, setting designs on the dobby. These are specific skill sets that are not acquired by all weavers. The few who do acquire them happen to be men.

The Handloom School is one such place where one could acquire these skills formally. It now holds a separate batch of training as well wherein the curriculum covers aspects of both design and business. Low levels of literacy and household care responsibilities are some of the major barriers that hinder the uptake of such initiatives. Even the ones who do undergo training, need an enabling environment at home to actually be able to take the leap.

0 Comments