“I ask you to leave your home, the clothes you wear, the family you love, and all that surrounds you because tomorrow, I will build a mall on the above the stacked pyres of your identity. You can’t fathom it. You won’t. Why must I? Why must your development come at the cost of who I am?” roared Janaki, a Maaldhari (pastorals) from the Rabari Tribe of Kutch.

Roughly 5 years ago, the first Pavanchakki (windmill) was installed. The proposed Clean Energy Project did not see enough hue and cry over its execution. The villagers, themselves unaware, were welcoming the development. It did not take long before the realisation that the windmills they welcome might soon call for an action against their installations.

‘Development’ always happens at the expense of those who are forcefully kept under the hierarchy.

The forest, in and around Sangnara village is abode to the locals. Both have been mutually harbouring each other for centuries. The flora and fauna resides in one of India’s most biodiverse patches of land. Additionally, the Maaldharis identify the land as gauchar or reserved for grazing. The folk derive their traditional medicine from the various herbs and shrubs growing. Their livelihoods, their identity, animals, and homes are deeply rooted in the forest.

Kutch has a gorgeous corridor for farming wind energy, the largest in Asia. Wind-farms have due considerations before being established. A prominent one in our case being, that it must not disrupt local homes, or grazing fields for livestock. Lo and behold!

There is a proposition for 80 such wind turbines that will fall right on the patch precious to locals, resulting in falling of 38,000 trees. Half of these have already been constructed and the locals of Sangnara and nearby 15-20 villages have been protesting to prevent the rest. Even the National Green Tribunal described the land as conveniently skewed in the maps to permit the construction of a wind-farm.

The ecological ramifications of wind farms are not many. The popular belief in the scientific community is that they are generally safe. Cattle have been found grazing right at the foot of the turbines. However, the ecological discourse is diverse, and perhaps the reader should do their own research. Here, shall be a space for the social ramifications, with perspectives of women at the fore.

In the past 5 years, the Maaldharis have continuously lost land and their protests have been gaining traction (although, still not enough). In one such protest that I joined, I saw a gallant collaboration of Sangathans (groups), Panchayats and organisations.

Janaki, initially was hesitant to speak. Comedy of errors, my broken Gujarati led her to believe I am here from the anti-side. She asked me to leave and so I did. After the procession and speeches were over, Janaki looked for me and said that she will now answer my questions. Happily, I agreed and reassured that I have neither the power nor the intent to construct any windmills in her land. She looked unfazed and confident, and said, “It doesn’t matter. If you are good, you could just smile. But if you’re bad, then I will change your heart.” A fierce response indeed.

I started with the basic interview-like questions. Why are you protesting? Why are the windmills bad? What do you do? Interesting answers to each. These basic sentiments were echoing similarly in the entire protest scape. I still wasn’t getting that perfect response to how does the windmill construction affect your life as a woman? As with all scenarios in my life; dimaag ki batti lit up a little late. She kept saying she will lose her animals that she has loved like her own children. “If my cows don’t give me milk, how will I feed my family?”

It is not that hard to miss, and yet I did. It is so obvious, yet, it isn’t.

In a family, where the woman is a caregiver, taking away that role from her will obviously upset her. If we go by the Hello Sakhi Helpline data of the past two years, or even by my own anecdotal experiences, when livelihoods are taken away from a family (whether because of lockdowns or a construction of wind turbines), the net suffering of the family ends up being projected on to the woman, at least in the current prevalent patriarchal set-up.

Janaki’s friend giggled across, “My husband gets irritable if food is not on the plate. (Smiles) Sometimes he’ll even throw a tantrum that it isn’t his favourite meal. Favourite meal 7-days a week? I am not a magician.” The conversation was longer than these couple of sentences. However, what continues to ring over and over is just a simple fact about food on the plate (or lack thereof) can ‘butterfly effect’ the well-being of women.

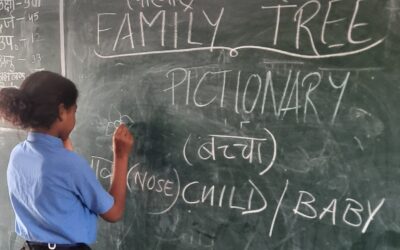

However, let me add this really really really heartwarming fact. Women and children are at the forefront of these protests. They are not weak. They are not scared. In Ariana Grande’s words, “I want it, I got it.”

0 Comments