By Aishwarya Chordiya

Introduction

‘Researcher for Cashrelief.’ A year and a half later, this continues to be a huge part of my identity. No matter what I do, this will always be one of the coolest things I have done and a constant part of my introduction. From September 2017 to December 2018, I studied 160 families for India’s first effort on unconditional cash transfers to alleviate poverty.

During the richest and most satisfying times of my life – I failed on a fundamental personal and professional value. I failed to live up to the research ethics I promised myself. I was in charge of studying almost all aspects of the lives of 755 people. I researched and documented everything – livelihoods, relationships, socio-economic issues and even hopes and aspirations. On many days, I even lived this life myself. Despite speaking the language of my community, I failed to clearly communicate exactly how I would use all this candid information to write their stories and who all would witness them!

I am sharing this story of my failures to acknowledge my (in)experience with research ethics, consent and privacy, connect the information gaps and fail better next time!

How It Played Out

The concept of daan (charity) is part of most of our lives growing up, especially in India. For me it started with donations to orphanages and old-age homes during birthdays or death anniversaries (shraadh), Diwali/Christmas gifts to the society watchman or distributing ration during devasting natural calamities. Little did I know then, a lot of it included blatant poverty porn. One time my uncle took me and my cousins to distribute blankets during winters. Despite spreading warmth, I remember feeling uncomfortable. We clicked pictures with shabbily dressed children, who were asked to pose while we gave them blankets. At another instance, I was in a slum teaching my domestic help’s daughter English when a few surveyors barged in and started asking the Didi questions and making notes. I only learnt the vocabulary to describe my ‘uncomfortable feeling’ when I formally started volunteering in college. It was poverty porn.

Since then, I am lucky to have closely witnessed and become a part of the stories of many didis, bhaiyas and children from the three NGOs I worked in and the others I volunteered for – including a rehabilitation centre, a home for destitute women, and a school for the visually impaired.

The experiences, stories and people couldn’t have been more different. Yet, my feeling of discomfort remained the same. Most times, questions were asked, entire surveys were conducted as if the details were owed to us. There was no permission required for clicking photos or recording videos. During that time, a friend once asked me something about privacy and consent and I just plainly replied, “we have bigger battles to fight here.” Honestly, the organisations I mentioned do incredible work with addicts, liberated manual scavengers and people with disability. There’s no question about their intentions, however, I continued to doubt (the lack of) research ethics. Yet, I quicky learnt to forgive them and even myself. I mean what is even enough in our line of work?

I was not able to forget. I joined the India Fellow Social Leadership Program. I spent my fellowship year trying to build dignified livelihoods. The different blocks of the fellowship – being on field with the communities, engaging with the organisation team, the speaker sessions and discussions that followed with my co-fellows over chai and personal reflection helped me channel my years of discomfort, questions, understanding and experience. I graduated from the fellowship with clarity of just one thing. All my work and ‘giving’ would ensure dignity.

Almost as if the universe was listening and Cashrelief happened! As a researcher for Cashrelief, I did a comprehensive baseline assessment of 160 households to identify the control and target families. Basically, spent the entire day for 5 months in the four selected hamlets – becoming a part of the lives of the villagers and in turn becoming a part of their stories. Based on this initial data, we selected one hamlet of 38 families to whom an unconditional one-time cash transfer of INR 96,000 was made. I spent another few months to understand how the families spent the money, their thoughts and plans for the future. In all this while, thanks to the co-founders and my mentors, I had complete freedom (and ownership) on this field research. My primary interviewees, the oldest working women (to whom the transfer was to be made) were always busy. So, I did interviews whenever they had time – while harvesting corn in the farms, at night post dinner and once even at a wedding function!

The first two weeks, were the hardest. The women refused to speak to me, the men were unapproachable and the children used to run away from me (they thought I was from the anganwadi and would give them injections!) As my face became familiar, slowly the children and then their mothers started speaking to me. Initially, all the villagers including the Panchayat members had a lot of questions for me. I answered everything to the best of my capability – without obviously directly mentioning Cashrelief, so as to ensure unbiased answers.

As I started fitting in, the questions reduced. Looking back, I realise I may have been familiar yet continued to be strange. From giggling at my questions, the women were giggling with me as they urged me to get married! Even though the community shared their deepest sorrows of domestic violence and sickness to their biggest joys – I failed them. I did inform the families of the research I was doing, how it would be shared with the government authorities and other NGOs/organisations who want to work in their area. And we obviously did all that!

I failed to communicate clearly to the community that their information, stories might be published (online) and would be accessible to everyone interested and the repercussions of that. It is a complex and hard conversation and I tried, but did not succeed. My inability to adequately follow research ethics I so personally valued, led to this communication failure.

I am unable to point out a definitive incident when I even realised my failure. Was it the time when I clicked Narda Didi, her children and mud house’s photos without elaborately explaining where, how and why I’d use them? Or was it when I stayed over at Bhuri Didi’s house one night after completing my survey and conducting an unstructured interview which I used to build a case study? I failed to properly explain to Bhuri Didi that her story might be written and shared online … where it will remain forever. Research ethics are complex. I have questioned myself more than the total number of surveys I conducted … there is no possibility I would be okay if I was in their place. Perhaps then a lot of complicated research ethics are as simple as common sense.

I am confident of the quality of the data and stories we collected because I completed the survey in multiple sessions, validating previous responses from the women themselves and also other family members. After the initial few days, although I continued to look different, I grew familiar. I guess so did my survey forms and notepads. My conversations were never limited to the actual questions. What if Bhuri Didi did not want me to share a few details of her domestic violence experiences with the world or write about it but not under her name? Maybe had I better explained the dreams and aspirations mapping to Kamala Didi, she would know that her hope of starting an enterprise and employing her neighbouring women makes her truly inspiring and forward-thinking? It stings me to have failed to provide information to my community which could enable them to see their own reality! These details that I missed would have allowed my community to make an informed choice of the agency of their stories – then and forever.

Cashrelief appeals to me since choice, for me is the most dignified way of ‘giving.’ I feel while we disbursed cash to the community, I took back something much more valuable … their life stories! Yet, by telling me their tales and tragedies, my community made me a part of their stories. As a researcher, I am accountable to them. Will always be because these principles will guide me, my actions and choices. It is my social responsibility which I have failed at. Although unknowingly, I feel I treated my community who is so dear to me even today with less respect.

What Was My Role In The Failure?

I began the research with no plan. I used games, helped in the farm work and even lived with a few families. I did not even realise when I got attached to these methods and was not ready to let go! It was not apparent then, but in hindsight I realise that I straddled efficiency and empathy. It was easier and efficient to not focus on innovating ways and methods to communicate the myriad uses of the shared information – as I had done for the research. For a lot of reasons including the nature of the work and even my approach, I had no ‘office hours’ and technically my ‘work’ had no end. While spending so much time with the community, I started assuming that a lot of things were just understood.

Cost Of The Failure

Thankfully, my failure was personal and did not directly impact the research, my organisation, team or funders. All the findings were published transparently including the raw data. To me, this failure is that ‘uncomfortable feeling.’ The guilt is intense on some days. On most other days, the failure influences my behaviour and actions and I continue to work on an initiative to communicate research better and make it accessible to everyone involved.

Happy Ending … Not

As I walked to the hamlets each day to my community for ‘work’ and also to attend weddings, SHG meetings, harvesting corn and once even a funeral, my community walked straight into my heart. As a researcher I had nothing to offer, only questions and a listening ear; my community managed to share with me their stories, food, festivals and pain – all with a smile. While in the community, bathing in the open and sleeping with houses with no doors, some part of me was still operating from a place of fear. Fear of not knowing, fear of making mistakes. I still don’t have answers for my questions, but the strong faith by my community has weakened my fear of making mistakes in field.

The nature of poverty is such that it demands immediate attention. Most of the Cashrelief community struggled with managing milk for the afternoon tea or flour for dinner rotis – privacy and the long-term policy implications of the research data they provide is not high on priority. As a researcher aware of the possibilities of the future opportunities and issues of the stories being shared – it was my responsibility to share that with my community. I knew it then, but only understand it now that the courageous thing is to be courageous and ask for help.

Although there is no happy ending to this story … yet, a silver lining is that I am learning to be more forgiving. To myself and others. The warmth of my community reaches me even today – as I am thousands of kilometres away each time, I speak to someone from the field. Each of these conversations helps me embrace my failure.

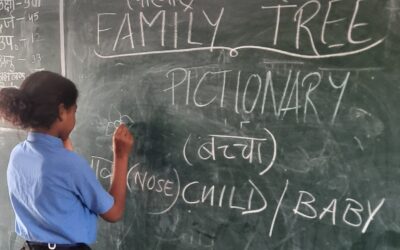

*** The cover photo is clicked by Amrit Vatsa, of one of the beneficiaries of the Cashrelief intervention

0 Comments