Nine billion tons – that’s the amount of plastic we have created since the large-scale production of synthetic materials began in the early 1950s. And why not, after all plastic is lightweight, flexible, relatively inexpensive, and durable, which also means that it almost never really goes away. This is why, of the 9.1 billion tons, more than 6.9 billion tons has become waste. And of that, 6.3 billion tons has not even made it to a recycling bin.

For anyone living in 2021, plastic is nearly impossible to avoid. It lines, leaches out of storage containers, hides in household dust, and is found inside of toys, electronics, shampoo, cosmetics and countless other products. It’s used to make thousands of single-use items, from grocery bags to forks and candy wrappers.

The future has to be sustainable and it shouldn’t be a question of “if” anymore. Instead, the question is, “is it too late?” If we think that we are doing ourselves and the environment one good by simply throwing our plastic bottles away into a large box marked with a recycling sign, in reality, it’s like taking only one bite of a gooey chocolate cake – we indulge, but not that much.

This is because recycling is a lot more complicated, and the process of recycling plastics is significantly less transparent than the much-Googled recipes for Dalgona coffee or banana bread. Similarly, our faith in the magic of recycling bin has only been making the purchase and use of plastic products a little more guilt-free.

From consuming a lot of energy, coming with its own share of pollution to leading us with low-quality plastic products, recycling simply isn’t netting the economic or environmental results we hope for. Think about the typical life cycle of a plastic item. You buy it, use it, after a while it breaks, and then you probably throw it in the trash. But what if the product was designed so that it could be repaired or more efficiently upgraded. Enters up-cycling.

Instead of defaulting to the “take-make-waste” economic model, upcycling is a fresher and more productive solution to promoting sustainable businesses and supporting the development of a circular economy. With a circular economy, the plastic that is already in circulation gets continually re-used and repurposed, helping to reduce manufacturing costs and preserve precious environmental resources. Providing a coherent framework, it thus provides an opportunity to harness innovation and creativity to enable a positive, restorative economy.

One of the greatest design challenges of our century is how we take things from one form to another, with no loss of value.

It is a philosophy shared by Khamir, a crafts-based NGO in Kutch, Gujarat, that is leading the charge, and their efforts are mirrored by other brands like Théla and ReCharkha, both of which too have turned to upcycled plastic textile to create products. Think mats, coasters, pouches, handbags, totes, footwear, and more. Often stitched and lined using old sarees and fabrics, these “upcycled” pieces have an artisanal feel lacking in many luxury goods.

By moving away from new material, whether it is cloth for handbags or plastic for shoes, Khamir was the first to create an opportunity for waste plastic which would’ve otherwise spent the next 1000 years in a land-fill, continuing to release methane gas.

How Khamir is Leading the Upcycled Textile Revolution

It all started when Katell Gelebart, a renowned French eco-designer visited Khamir and expressed interest in developing products from waste produced by artisans. In Katell’s research, it was found that Kutch’s artisans have always been sustained by locally available raw material, and that they were experts at reusing it, making their production nearly “zero waste”.

Also read: From waste to wave

However, over the years, artisans started getting their material from industrial processes and not from their own surroundings. The focus then shifted to the larger ecosystem of Kutch, to find ways to create value from waste. Having witnessed plastic as a freely available environmental nuisance, Katell wanted to integrate the traditional skills of artisans towards developing items of use. That’s how plastic went on to get upcycled as a textile.

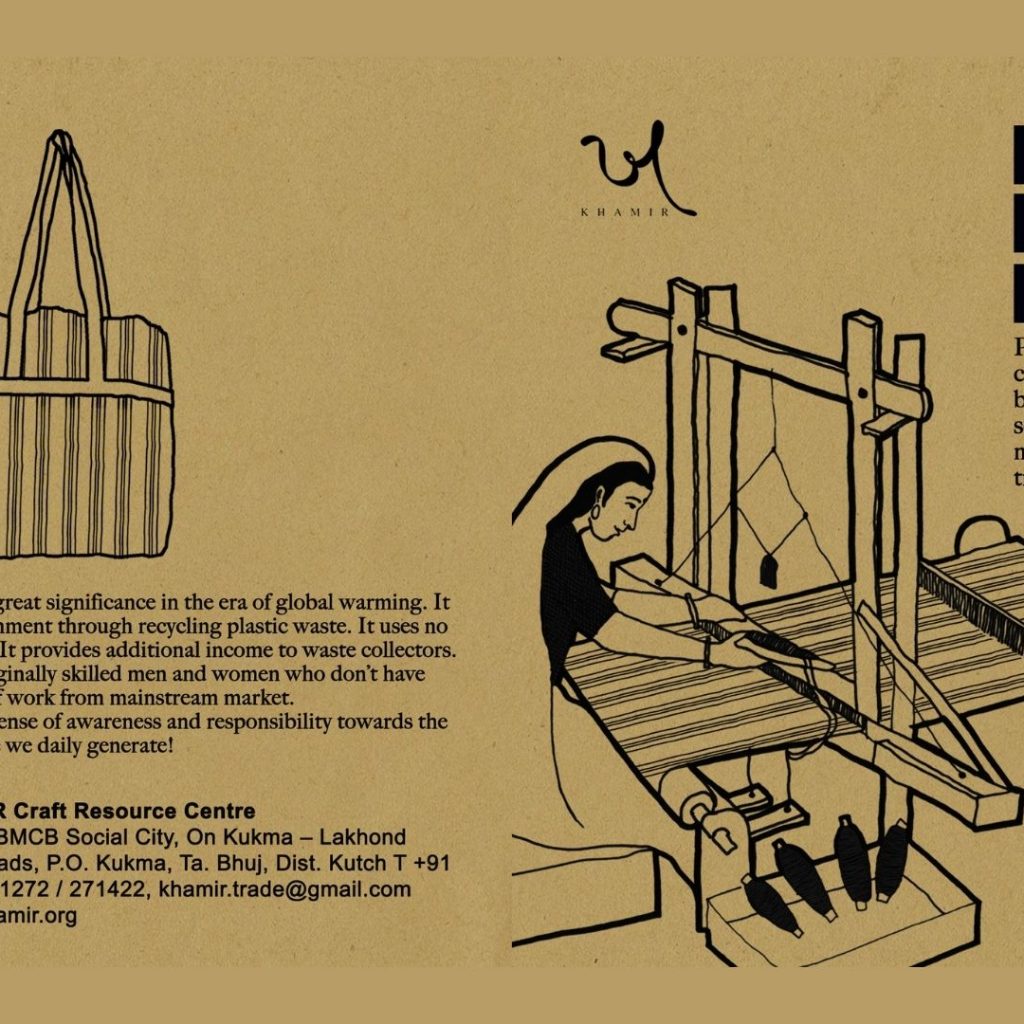

With over 2000 looms spread across Kutch, and handloom weaving being one of the traditional handicrafts, it was an ideal option to integrate with plastic. After many trials and errors, a process was finally formulated to upcycle locally collected plastic bags and cement bags into high-quality products. It also meant rethinking product design, showing how it can go a long way in extending the life of a plastic bag, and making it the norm.

Designed around sustainability, the model developed was energy-efficient in comparison to recycling as it took discarded plastic bags and then converted them into different products that would last longer, with increased utility. Rather than creating new material, this intervention found a way to protect the local environment from harsh toxins that modern production technologies otherwise produce.

But just committing to give back to the environment was not enough for Khamir. What started in 2006 as a pilot, went on to become an Upcycled Plastic Weaving initiative, which has since been helping promote the ancient craft of weaving in tandem with the local ecology of Kutch, and facilitating forward linkages that provide sustainable livelihoods for many along this newly created value chain.

Initially, as part of this initiative, Khamir trained two women weavers and has since built capacities of more than 100 people, many of whom do not belong to the Vankar or weavers community of Kutch. As it’s mainly a skill-based craft, this initiative managed opening up the possibility for a wide number of people such as medium-skilled weavers, home-based workers, disabled and senior citizens who continue to get trained from Khamir.

Khamir has also been offering technical and fiscal support that may be required to set up handlooms. Over the years, the organization has even held trainings across the country by collaborating with other organizations such as Atapi Seva Foundation of TML Industries Limited, the Palara Jail in Bhuj and Aarohana Eco-social.

As an organisation, Khamir believes that upcycling should be thought as an integral part of a value chain rather than as a cultural technology. To cut a long story short, the importance of upcycling increases to the extent that the awareness for saving resources and circularity rises on the market. Local plastic collection drives in association with other local NGOs and CBOs prove to be an efficient means to conduct awareness campaigns that bring together multiple stakeholders who are tied by the common thread of plastic, thereby creating a nexus of local impact.

Making New from Old

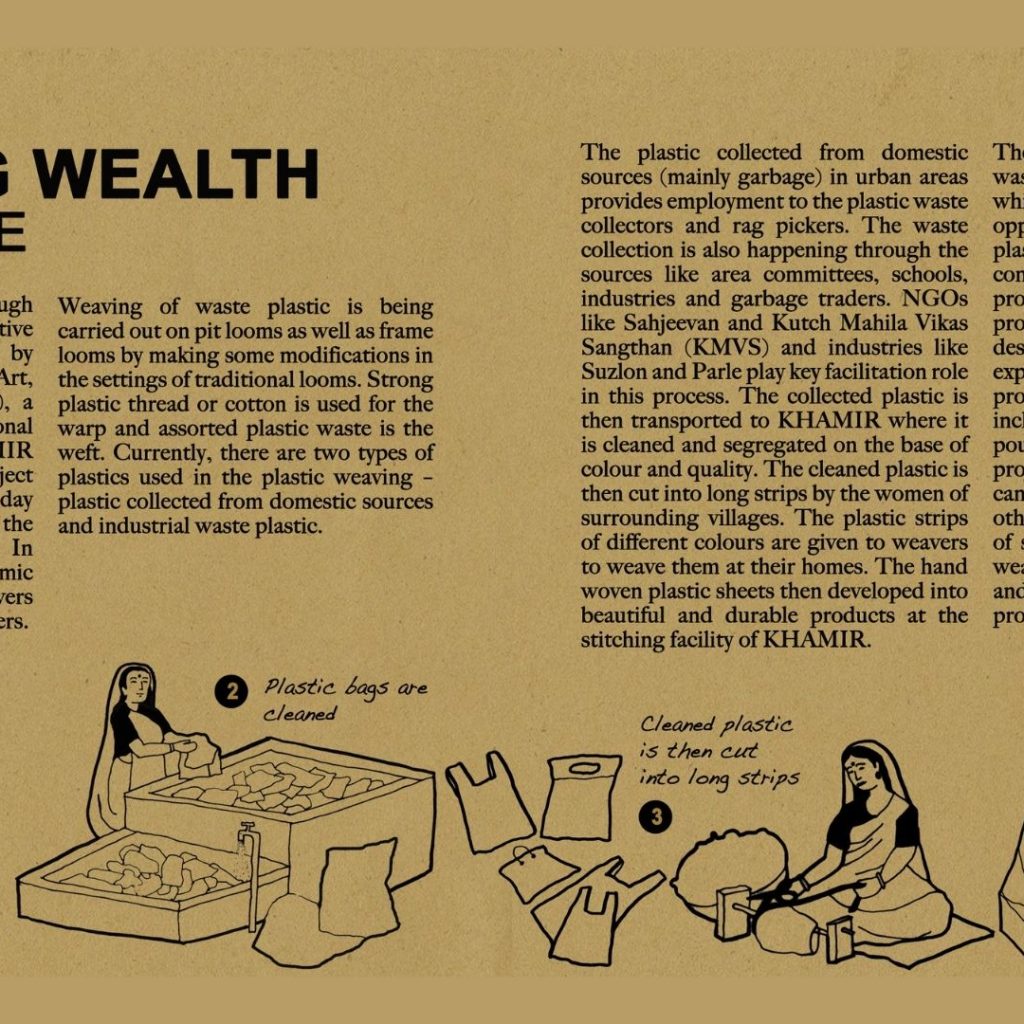

Khamir locally sources its plastic and in the bargain, also provides sustainable employment to waste pickers, and scrap dealers. The collected plastic is then transported to Khamir’s campus where it is sorted since only the one between 40-100 microns is suitable for weaving. The plastic is then cleaned by hand using mild detergent and water by Nanu maasi, who is also a weaver. The washed plastic bags are then sun-dried for an entire day.

After drying, the plastic is sorted according to its grade and colour, and is then readied to be converted into yarn. This is done by rolling the plastic on a rod and cutting it into long strips using a cutter or scissors. The cut plastic is then collated around the thumb and the pinky finger creating a yarn which is then wound on a spindle using a charkha.

As plastic is difficult to weave, nylon yarn is used as a warp. Other materials such as local wool or jute are also preferred for warping. The woven plastic sheets are then shifted to a stitching unit, where tailors produce a finished products out of the fabric thus woven. The products that are made are often focused on innovations that are unique, small, efficient and solve a purpose.

Take for instance, the inter-linking of other crafts such as desi leather work, turn wood lacquer and ajrakh block print with that of upcycled plastic weaving. Additionally, since most of the women weavers are skilled in Kutch’s famous extra weft weaving technique, Khamir has incorporated the same in its products in the form of Kutchi motifs and patterns, adding to the story of the product.

Also read: Handicrafts: The Colored Jewels Of Deserted Kutch

And yet, because there are a few economies of scale and even fewer production systems, such upcycling remains for many designers an experiment rather than a strategy, and for many consumers, a luxury rather than a choice.

In its endeavour to make a real difference in terms of plastic’s impact on the environment, and to encourage more brands and organisations to follow suit, Khamir has also been helping other individuals, social entrepreneurs, and non-profit organizations transition from a linear to a circular business model, and to do it profitably.

Khamir provides a list of resources in the form of manuals and brochures to help others take a step towards building environmental consciousness and economic upliftment through sustainable measures. These resources aim to give a holistic insight into the framework of upcycling plastic using traditional weaving so as to encourage anyone replicate this initiative in their context.

By taking the lead on upcycling, organisations could add a new dimension to the industry and help solve the problem of plastic waste. Under a scenario where much larger quantities of plastic waste are routed for reuse instead of going to landfill and incineration, Khamir sees the potential to transform three areas:

- Solving the plastic-waste problem,

- Encouraging a circular economy, and

- Attracting young people to take on weaving

0 Comments