India’s steel industry is a key pillar of its industrial and economic growth, making it the second-largest steel producer globally. The industry has a robust annual production capability of over a hundred million tons impacting sectors which include construction, automobile industries, infrastructure, and manufacturing. India is a major producer of both carbon and stainless steel, with stainless steel growing fast on the back of increased urbanization, industrialization as well as government led infrastructure development.

West India particularly Gujarat, Rajasthan and Maharashtra has emerged as major hubs for the steel industry, because of easy access to ports and raw materials. The growing automotive, petrochemical, and construction sectors are crucial drivers, while the region’s proximity to major international markets enhances export potential.

Jodhpur’s Industrial Landscape

With a total area of over 22,850 square kilometers, Jodhpur is one of Rajasthan’s largest districts. Jodhpur is mostly a desert region that experiences harsh summer and winter climatic conditions. A rich concentration of non-metallic minerals, such as sandstone, limestone, dolomite, and other minor minerals, is also observed in the district. Jodhpur district’s small-scale industrial estates and locations are described in depth in a consolidated report that was created by the Ministry of Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises in 2020–21. The paper gives a good overview of the area’s topography and the kinds of units that are located there. It also offers trends for registered units by year, capital investment information, etc.

The report lists 23 industrial areas or clusters in Jodhpur, all of which are developed and overseen by the Rajasthan State Industrial Development and Investment Corporation (RIICO), a state-sponsored initiative that aims to increase investment in the state of Rajasthan’s industrial sector by giving direct access to information on contracts, directives from the government, and other press releases pertaining to industrial sites that the corporation owns and operates.

Small-scale industries employ the majority of the workforce. Much of the workforce comprises migrant workers from Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, and Rajasthan’s nearby districts, working in hazardous conditions for modest wages. Wages vary between ₹300-₹500 per day, with contractors handling recruitment. Working conditions are tough, often lacking adequate safety measures.

Surja Ram: A Steel Worker’s Journey Of Grit, Growth, And The Fight For Social Security

Surja Ram’s story begins in Bher village, nestled in the Osian Tehsil of Jodhpur district, where he was born in 1983. A humble beginning saw him leave school after class 5, as life’s pressing realities beckoned him towards earning a living. At just 18 years old, in 2001, he joined Chetan Industries, a steel manufacturing unit where 300 to 350 workers toil daily, shaping steel and their futures.

A Path Forged Through Family Ties

Surja Ram entered the world of steel work through his uncle, Hemta Ram, who helped him find employment in Chanchal Industries. At the time, he started with a meager daily wage (हाज़िरी) of ₹70, or about ₹2,100 a month. Over the years, his wages improved steadily, and now he earns ₹15,500 per month.

However, as a piece-rate worker, he is fortunate to make even more. His monthly earnings often soar to ₹26,000, thanks to the flexibility he enjoys. He’s paid as a contractual worker but allowed to earn on a piece-rate basis as well, an arrangement that rewards his dedication and skill. Surja Ram reveals that on a good day, he can earn ₹1,200 to ₹1,500, a feat that would be impossible on a fixed wage system. For each steel sheet he finishes, he earns ₹200, crafting six to seven pieces daily.

“If I stuck to a monthly wage, I wouldn’t make more than ₹20,000–22,000,” he shares. His current flexibility gives him a decent standard of living, though the dangers of the job loom large.

Piece-Rate Work: A System Of Flexibility Or Precarity?

Piece-rate work refers to a payment system where workers are compensated based on the number of units they produce, rather than a fixed salary. In Surja Ram’s case, this system allows him to earn significantly more than he would on a fixed wage. He earns ₹200 per steel sheet, producing up to seven pieces a day, making his monthly earnings fluctuate between ₹20,000 and ₹26,000.

While the piece-rate system offers flexibility, it also brings insecurity. In such a system, a worker has to work for a minimum of 12 hours per day, in search for more income. They are not entitled to social security benefits, such as overtime payment, gratuity, PF etc. Workers are not paid during factory shutdowns, and there are no guarantees of a steady income. The system benefits employers by keeping costs low while making workers entirely responsible for their earnings.

Life On The Grinding Machine: A Lifelong Engagement

Since the day he started, Surja Ram has spent his entire career working on the grinding machine in the “Pata Line” of Chetan Industries. Grinding steel is grueling work, requiring precision and endurance, but Surja Ram has mastered his craft over the years. He’s proud of the life he’s built through his job, despite the risks and lack of safety measures in the factory.

He recalls the tragic incident when one of his colleagues lost his life due to a crane accident in the factory. “There is no safety equipment,” he says grimly. Workers arrange their own gloves and boots as nothing is provided by the factory. Over the years, Surja Ram himself has faced numerous minor injuries—cuts, bruises, and scrapes—while loading and unloading steel, but, fortunately, he has avoided serious harm.

The Battle For Social Security

While he may have grown comfortable with the hazards of the steel factory, Surja Ram’s fight for social security has been anything but easy. He understands the importance of social security benefits like PF (Provident Fund) and ESIC (Employees’ State Insurance), ensuring he has these accounts since he began working.

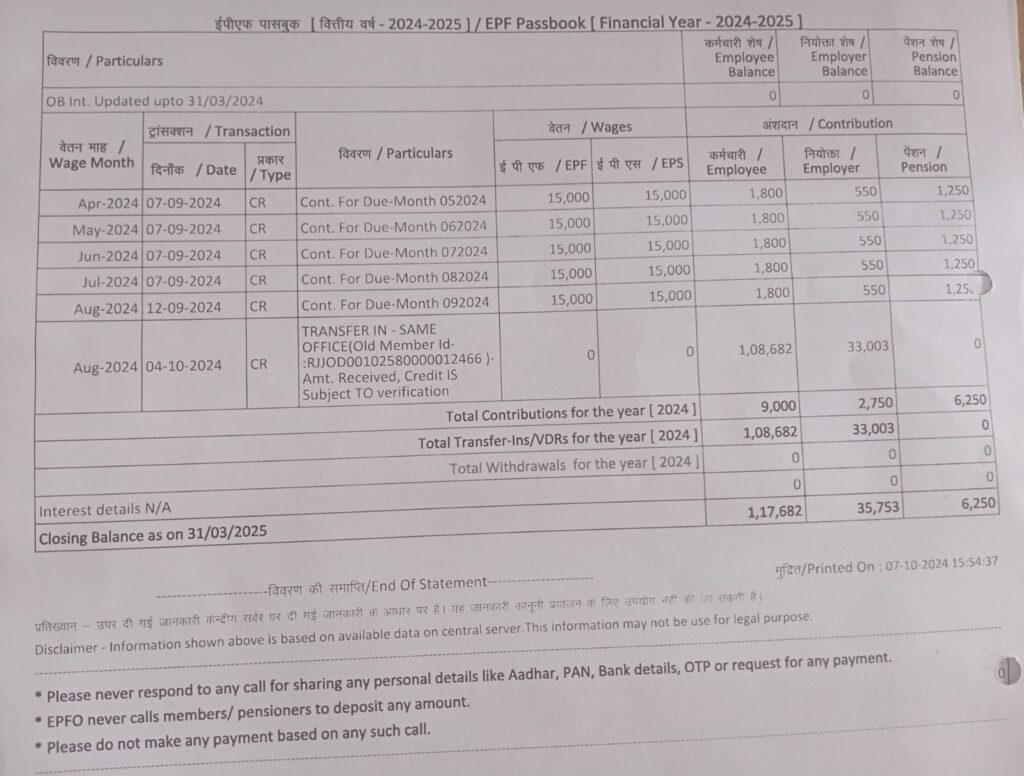

However in March 2024, Surja Ram was shocked to find that his PF contributions were stopped. The factory owner cited his salary increase from ₹12,350 to ₹15,000 in March 2024 as the reason for discontinuing his PF. However, Surja Ram wasn’t convinced. Determined to seek justice, he visited the PF office to clarify whether this was legally valid. There, he discovered that the factory was deceiving him.

Seeking help, Surja Ram approached the Aajeevika Labourline office, where he was assisted in filing a formal application. In April 2024, he submitted the application, and by September 3rd, officers from the PF vigilance department visited Chetan Industries to speak with the factory owner. Just two days later, Surja Ram’s PF contributions were reinstated, and he received ₹9,000 for the five months during which his PF was unlawfully withheld.

In September 2024, his salary was ₹15,930, and his piece-rate earnings amounted to ₹10,600 for 53 pieces of steel work—making his total income for the month ₹26,530. His PF contribution now stands at ₹2,552 per month. “My PF is the only form of savings I have,” he says. “That’s why I fought for it.”

Before the complaint was filed, the monthly Provident Fund (PF) contributions ranged from ₹5,270 to ₹7,750, as shown for various months between March 2023 and February 2024 in the left image. After the complaint was filed, based on the right image (starting from April 2024), the monthly contribution has been consistently recorded as ₹1,800.

A Family Man With Aspirations Beyond The Factory Floor

Surja Ram married in 2003, and today he is the father of three children, aged 15, 13, and 11. He sends almost 75% of his income back home to support his wife and children’s education, around ₹20,000 per month. His family now lives in the home he built in his village. He has even invested in jewelry for future emergencies. Over the years, his financial status has improved significantly. He takes pride in providing a better life for his family.

Surja Ram is deeply committed to his work. Albeit, he dreams of an alternate (better) future for his children. “I’ll never send my kids into the steel factory,” he says firmly. “I want them to study, to get good government or private jobs—anything but this.” He hopes to continue working until he is 60, though the challenges of the steel industry weigh on him. Yet, with upgraded skills and a strong work ethic, Surja Ram remains hopeful about the future.

Labourline: Advocating For Workers’ Rights

Labourline, an initiative by Aajeevika Bureau, provides critical support to workers like Surja Ram. The Labourline helps workers navigate legal and bureaucratic processes, offering guidance on issues such as non-payment of wages, lack of social security, and workplace entitlement. In Surja Ram’s case, Labourline played a pivotal role in reinstating his PF contributions when his employer stopped them unjustly.

Surja Ram’s story is not just about hard work; it’s about resilience and the understanding that every worker has the right of social security. His determination to fight for his PF benefits, even in the face of factory resistance, is a powerful reminder of the importance of knowing one’s rights. As Surja Ram Ji continues his journey, he serves as an inspiration to fellow workers. He proves that no matter how difficult the conditions, the right to social security is something worth fighting for.

0 Comments