8/8/18: It was my second day in Mishirpur, a village in Sitapur district of Uttar Pradesh. I was casually interacting with a male and a female member of a household, unaware of their social status in the village.

(The original conversation took place in a mix of Hindi and Awadhi)

Man: You must not go further into the village; there is a lot of dirt out there.

Me: Ummm, really?

Man: The lower caste people live there. It’s filthy. The place stinks specially because they own goats. As you can see, we have cows and keep our surroundings clean.

As I looked around, there was not much of a difference in the level of cleanliness. The distinction lied in the amount of space occupied by people from lower and higher castes. The latter owned large spaces at the head of the village, both literally and figuratively. They even had their own temples.

This got me thinking about the complexity of the caste system in Uttar Pradesh, or for that matter, the entire country. We cannot understand India without knowing the notions of purity and pollution related to castes. The hierarchy of caste system as well the practice of ‘untouchability’ are both based on such notions. The basic division of caste in Hinduism is as follows:

- The Brahmans or the priestly caste comes first

- Followed by the Kshatriyas or the warrior class

- Then there are the Vaishyas who are mostly merchants or landholders

- and then the Sudras and other castes who are considered untouchables.

The Sudras and other people from lower castes deal with work that involves dirt, blood, and even death. This was the basis to place them at the bottom of the purity-pollution vertical, considering that they are most polluted. On the other hand, the Brahmans are considered to be the purest of all as they serve God. Rest all the castes and sub-castes are ranked according to their relative level of purity which depends on their occupation. This goes on for generations, being hereditary in nature. There are several traditions based on this system which prohibit higher and lower castes to have sexual contact and even eating together.

Watch: Decoding Hinduism With Devdutt Pattanaik | Episode 1: Caste

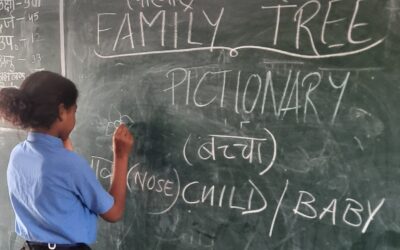

In Mishirpur, I discovered a lot about the system through interactions with men, women, and especially, children. At present, men of the village go out to work. People who have their own fields, go to look after them while those who don’t, work on other’s fields. Some of them go to the nearest town to work as laborers. Most people have moved away from their ancestral occupations. One can figure a link between the caste and the related occupation; however, there is nothing much left about purity and impurity of work. The system exists because of the Brahman traditions that have deeply penetrated into the society, mainly because the people from upper castes do not want to do away with their privileges.

Now, the basis of discrimination has also changed. First is the type of animals people own. For example, in the conversation narrated above, it is clear that the upper caste owns cows and buffaloes while the lower castes own goats. Second is the eating habits. If you are from a higher caste, you are supposed to take to vegetarianism. The non-vegetarian diet is mostly for people ranked lower on the purity levels. Additionally, there is a prevalent practice in this village to have a tattoo-like mark for elderly of the lower castes.

While having a candid conversation with a school student, I noticed his astonishment as he asked, “Ma’am how can you belong to the General category when you eat non-vegetarian food?”

The other day, during a parent-teacher meeting in school, a father was asking if the Mid-Day Meal (National Food Security Act, 2013 – Government of India) can be served to his child in a plate that the child will get from home. He expressed genuine fear about other children eating from the common plates on different days, and said that he was concerned about the “cleanliness” of the school’s plates. He had clearly implied that he did not want his son to be eating from a utensil which was being used by children from lower-castes or Muslims. Even though the school provides only vegetarian meals, his problem was the ‘purity’ of the other castes.

Most people whom I met here, consciously or subconsciously, are keen on knowing the caste I belong to, because that determines how they will treat me, whether I can enter their house, or if they need to take certain precautions in case I have already entered their house. There are several ways of finding out one’s caste. Usually, they ask your “full” name, which has to include your surname. It sometimes becomes an interesting puzzle for them, when I tell my name which does not have a surname. Then they go on to ask about my food preferences and patterns, making observations about me being vegetarian or non-vegetarian. I ridicule them even more by telling that back at my home, caste and diet have no relation. Some have gone further to solve the mystery by inquiring if my parents have the tattoo like mark on their hands, or if they own fields and cattle.

Through this experience, I saw how caste as a system, instead of dying down, has updated its rules to become stronger. While doing away with the earlier rules and taking up new ones, the system is co-opting dissent of the underprivileged. It provides a stronger foothold to those who were already at an advantage. The hegemony of the upper castes have made this system, the norm. People continue to get exploited without being aware of it, and its consequences.

Good Post! What do you think about prevalence of caste related dynamics in school especially amongst children?

PS. Plate thing was implemented only last year so definitely can empathise 😀

I have not felt the high dynamics school yet. Yes, sometimes when the teachers are casually talking about surnames and children of one village not wanting to go to another village.

Oh, and also I feel in some cases, caste has determined the basis of friendship (not applicable for a lot of children)

good read

Very intriguing perspective on how the divide is deepening in alternative ways. Well written Swati!

And the trend is so subtle. Kids ask me the same and I would never have realised their curiosity to know my caste if you hadn’t made it so explicit here.