When we hear ‘wool’, what comes to our mind? Perhaps, the feather-soft flowy Pashmina of Kashmir? Or fluffy round sheep grazing in green meadows? Or would it be an old grandma forever knitting away colourful yarns as a cat plays with strewn wool strands in the background? Would you think of wrapping up in a woollen blanket sitting by the hearth, basking in the warmth with your loved ones?

To humans around the globe, wool has different meanings and usages. Let’s take a closer look at wool much closer to our homes. Hamara Apna Desi Wool.

Where Does Wool Come From?

From the back of the sheep of course! But there’s more to its origin. To understand that, let’s answer a very simple question. What really is wool? It’s hair. Does that mean we have wool on our head? Then why don’t we make coats out of our hair? Because human hair cannot suffice. Early humans realised that we can create layers to help us adjust to the harsh environments. They figured – what better than a sheep to make the same? A wholesome companion, sheep provided for all the basic needs – meat and milk for food, skin and bones for clothing, shelter and tools. And it demanded very little care! Thus began the advent of the pastoral life. Having established that wool is essentially hair derived from animals, it’s important to understand wool can be sourced not just from sheep. With a geographical diversity as rich as India’s – the mountainous regions of north and northeast India, the arid terrains of Rajasthan and Gujarat in western India, and the Deccan Plateau, are home to a large population of wool producing animals such as sheep, goats, camels and even yaks.

What Do We Do With Wool?

India’s vast genetic resource of wool has been conserved and bred by the nomadic pastoral communities of these regions. Kutch, India’s largest district is predominantly pastoral. Here, the Rabari tribe herd camels, goats and sheep which are the largest contributors of Kutchi Desi wool. Like humans, sheep also need regular haircuts- at least once every six months, for the sake of their own cleanliness and well-being. Known as shearing, this is performed by the Rabari tribesmen. Shearing yields wool fibres of which the longer fibres get spun into fine yarn and reach destiny in the form of a woven or braided textile. The shorter fibres are ideal for wool crafts.

The Kutchi crafts are eloquent, narrating a story that brings forth deep rooted cultural ethos and traditions. Geographical isolation of Kutch has made it hard for the herding community to depend on the external world for their needs. These communities are mobile, spending most of their time outdoors. Thus woollens became the perfect choice of apparel for such living. Vibrant wool-craft economies evolved in response. Their nomadic way of life led to formation of strong ethos of self-reliance, fearlessness and sure-footedness which is reflected through their crafts. This in turn led to a strong culture of handcrafting using locally available materials. The wool craftsmen catered to both pastoral as well as other settled communities such as farmers. At the heart of this system lay community inter relationships, threads of interdependence that tied communities and economies together.

Kutchi Wool Crafts

CRAFT 1 – Hand Spinning is the craft of converting raw wool into a yarn – which are essentially threads that can be woven with each other to create a fabric.

- Step 1: The raw wool is traditionally washed with cow urine to soften it

- Step 2: Wool is being separated by hand before carding so as to separate the dust and burrs from it and align the fibres by hand as shown

- Step 3: It is then carded using the hand-carding machine to further clean and even out the fibres for better spinning. Carded wool is turned into a sliver which can be spun in two ways:-

- The Doshi Charkha is used by the women of Rabari community for hand spinning the hand sliver wool (video below)

- Rolling By Hand to create a thick and long sliver (windy) which is then further thinned out to convert into a yarn (takli). This is done by the men of Rabari community (image below)

Additionally, raw wool or the prepared yarn may be dyed black, indigo, red, yellow, green, brown all of which may be derived from natural sources. Dramatic colours add energy and dynamism to an otherwise arid landscape of Kutch.

CRAFT 2 – Handloom Weaving – The wool yarn is handed to the village weaver who stiffens the yarn with wild onion extract and custom weave products such as shawls, skirts, blankets, rugs, carpets and headgear. Interestingly, these clothes used to be worn in summers too because the fabric would be woven to let air in and keep the body cool, a property only exhibited by Desi wool. Handloom weaving in Kutch is so diverse and unique, it’s shawls have now received their very own GI tag!

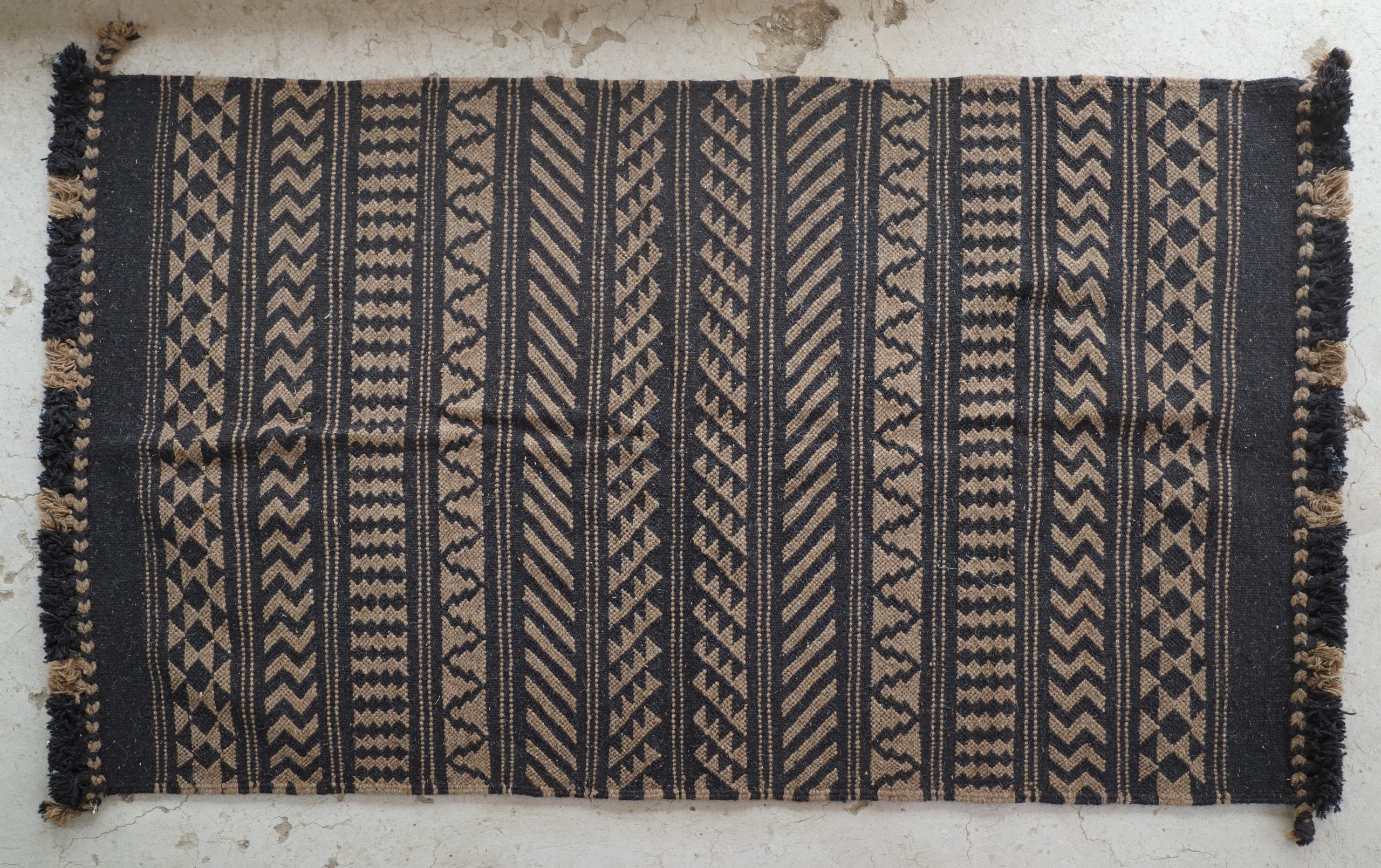

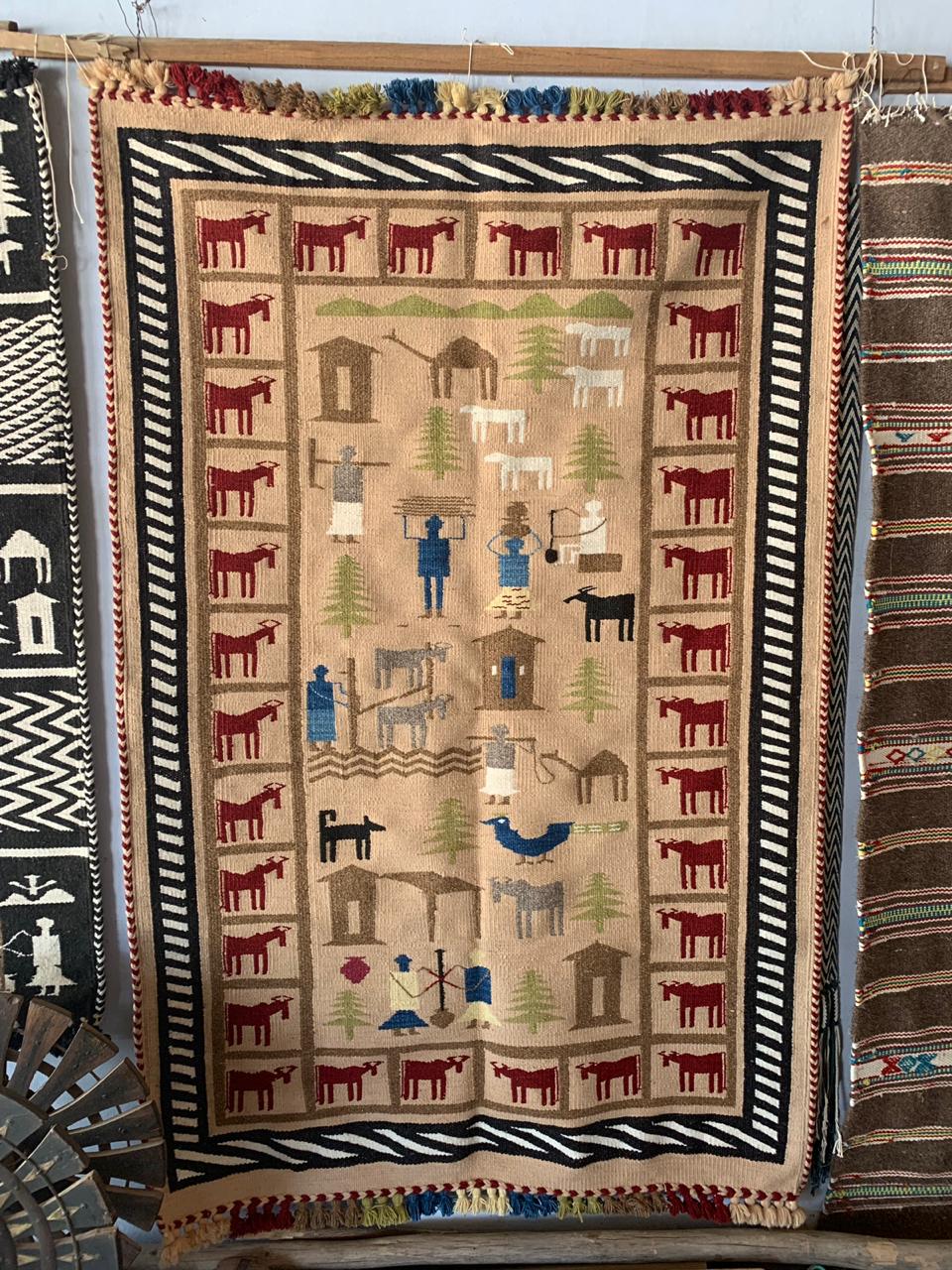

Owing to the different forms and styles of weaving, let’s take a look at the subtle nuances in them. CRAFT 3 – Kharad rugs are traditional rugs made from camel and goat hair; produced on special nomadic looms. Kharads often last for a hundred years.

CRAFT 4 – Ludi Veil A Ludi covers the head of the wearer and often the face when in the company of strangers. It is living proof of close-knit communities – the nomadic Rabari spinners and embroiderers, the Meghwal weavers, and the Khatri dyers. All of them come together to produce a Ludi. It conceals the key to nomadic survival – the unknown should not be trusted.

CRAFT 5 – Tangaliya Often mistaken for embroidery, is the art of creating spangle-like beads on a woven surface by twisting small lengths of extra-weft onto the warp threads. These spots of colour come together to narrate a story of trees, birds, and animals. Traditionally, crafted on skirts worn by women of the Bharwad community, Tangaliya has found its way into shawls, blankets and other garments.

CRAFT 6 – Dhabdas are multi-purposed – shoulder cloth, rug, carrier, mat, blanket, and rain cover. Intended to be used outdoors, they are woven tight to last long and keep the wearer dry and warm.

CRAFT 7 – Tabariya Are herding bags which utilize techniques of both ply-splitting and weaving. These bags are tied around camels and hold items that the herder would require through their herding journey. Since these herders are always on the move, they found a way to weave without a loom!

CRAFT 8 – Namda (Felting) Traditionally, Namda was used to build framed saddles which helped distribute the rider’s weight on the back of horses and enhanced the potential use of horses in warfare and long-distance travel. A physically strenuous craft, Namda requires no stitching at all.

CRAFT 9 – Embroidery The picture shows Bharat Kaam being done by a Rabari tribeswoman. Kutchi embroidery is amongst the finest in the world. Embroideries are also very personal as they are community memories, rituals, values and experiences embedded on to the cloth. It is also a statement of belief in beauty and a way of expression for local women. Wool embroidery creates appealing surfaces and textures but is not popularly practised anymore.

The Dying Wool

Like all things indigenous, the Desi wool too has suffered. A deeper look at the crafts from the lens of creation would find complex inter-dependencies and a creation of expression and purpose. However, Desi is has now become a term often looked down upon as “inferior quality”. This came into picture through a narrative, that triggered the downfall – a blind greed for superior quality. Although India has the third largest population of sheep, the 40 million Kgs that is produces annually, is in fact coarse wool suited best only for carpets, rugs, thicker textiles crafted and hand-woven products.

When the foreign Merino wool was brought to India, we realised that woollen garments could be made finer. Thus began the spiral. Import duties have fallen down to a staggering 15%. Cheap wool import from the Middle East and China has been constantly growing and the former is often mixed with indigenous wool to make hand tufted carpets, thus entering the domain of Desi. Imports of wool have surpassed what India itself produces. The other side of the problem is reliability of supply of Desi wool. Of late, there has been an increase in burr and dirt in raw wool. Thus, the percentage of wastage is unpredictable from region to region making it difficult for traders to source Desi wool.

Across the world, there has been an increase in demand for sheep meat. With Governments promoting meat breeds over wool breeds, pastoralists have, over the years, begun to cross breed their native breeds or maintain a larger flock of meaty breeds. Although India remains one of the world’s largest exporters of goat and sheep meat, production of Desi wool has decreased in all the major wool producing States, except Telangana.

Taking a closer look at Kutch, the Patanwadi breed is rapidly becoming a less-preferred choice by herders as compared to other breeds due to several reasons. One such reason is that Patanwadi sheep are not good climbers and, with increasing encroachment and industrialization resulting in dearth of flat grazing resources, the sheep has turned out to be a liability. Despite the fact that the sheep is hardy, its meat producing ability is limited. Furthermore, the lack of niche demand for its milk made it less popular among the herders despite its ability to produce decent amounts of milk. In addition, while it is the best producer of wool, there is hardly any notable economic value for its wool.

Penning, an age old practice, is on a decline due to an increase in use of synthetic fertilisers as well as the rapid spread of Prosopis Juliflora, an invasive woody specie; Prosopis Juliflora pods ingested by sheep and goats undergo scarification and spread Prosopis faster, an event that no farmer takes a liking for. Consequently, the number of sheep per herding household has gone down. The associated handicrafts are quietly fading away. There is little will that remain in herders or the artisans to see their offspring carry on this style of living. They now find themselves at the mercy of a global economy that fluctuates and of which they understand little.

Can We Save The Dying Ecosystem?

Ever since the cross breeding, herders have realized that the new breeds are in fact more vulnerable to disease and less resilient than the hardy local breeds. These Desi breeds bear an indispensable genetic resource pool which is at the verge of extinction. With increased climatic volatility, going back to an ecosystem where sustainability and inter-dependence is a way of life, has become imperative. The primary step is the restoration of the ecosystem as well as apt market linkages that support the Desi herders and their crafts. The network of organisations in Kutch is a quintessential example for this. Laced with empathy and urgency, efforts have been taken by groups like Khamir to revive dying wool-crafts and Sahjeevan‘s many initiatives to restore the pastoral ecosystem. These efforts are focused on weaving new threads of interdependence, bringing about cohesive and holistic growth. To know more about these initiatives, stay tuned for the next blog.

If you want to know more about the Desi Wool of Kutch, watch the video below:-

*Source for research materials and photographs Khamir, Centre For Pastoralism

0 Comments