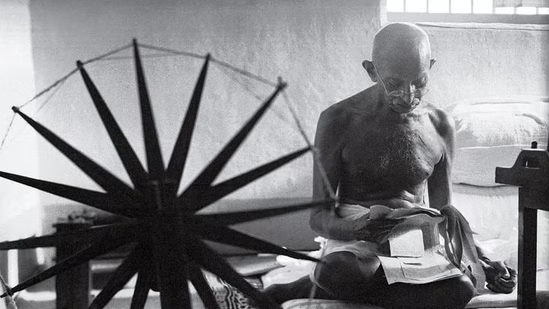

When we hear the name Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, we imagine a lean old man wearing a dhoti, bare chested and carrying a wooden stick. But there is much more to Gandhi—his principles and the ethics he lived by. After returning from South Africa in 1915, Gandhi began traveling across India to better understand the country he had left many years ago. During these travels, he witnessed the extreme poverty in rural India and observed how the colonization had devastated local industries, particularly the textile industry.

Gandhi’s relationship with charkha (spinning wheel) was not just symbolic, It was deeply rooted in his idea of self-reliance. He saw it as a means to empower rural populations who suffer greatly because of British policies to destroy the Indian textile industry. By promoting spinning of charkha, he wanted to counter the British dominance on textile industries and make India self-reliant.

Swadeshi Movement

In 1917, Gandhi decided to learn how to use the charkha as a way to restore traditional crafts and revive the rural economy. It was Gangaben Majumdar who introduced Gandhi to the art of spinning and personally taught him how to use the charkha. Initially Gandhi struggled with spinning charkha but with perseverance he became proficient. Gandhi soon understood that spinning charkha was not merely an act of producing the clothes but a means to bridge economic divide and gainfully employ millions of people.

Charkha played a crucial role in the Swadeshi movement. He urged Indians to boycott British goods specifically in textile and instead wear khadi. Gandhi himself adopted this and wore only dhoti made of khadi which later became the symbol of British exploitation. He encouraged people across the country to take up spinning, believing that if every Indian spun for just one hour a day, it would break India’s dependence on British goods.

The charkha ultimately became a symbol of resistance against British rule. It was incorporated into the Indian National Congress flag in 1931, signifying the movement’s commitment to self-reliance. Even after independence, Gandhi continued to advocate for khadi and village industries, emphasizing that true freedom meant economic independence for every Indian, particularly the rural poor.

with a charkha in the foreground. (Photo courtesy: National Gandhi museum)

GSS And Charkha

Gram Swaraj Sangh (GSS) has always upheld the Gandhian value and integrated it into the daily life of its students and employees. One way they do this is through the shramdaan (voluntary labor) and morning prayers. All the elder members of the organization are present with all the office staff. We begin the morning prayer with spinning charkha followed by prayer, bhajan and discussion on Gandhi.

All the big decisions at GSS happen in Gujarati, and my brain often plays a game of “guess the context” (and loses). I’ve confidently misinterpreted discussions more times than I can count. After five months in GSS I can say that I can understand Gujarati. Also, morning prayer attendance is non-negotiable—so I start my day with devotion…and a desperate need for coffee.

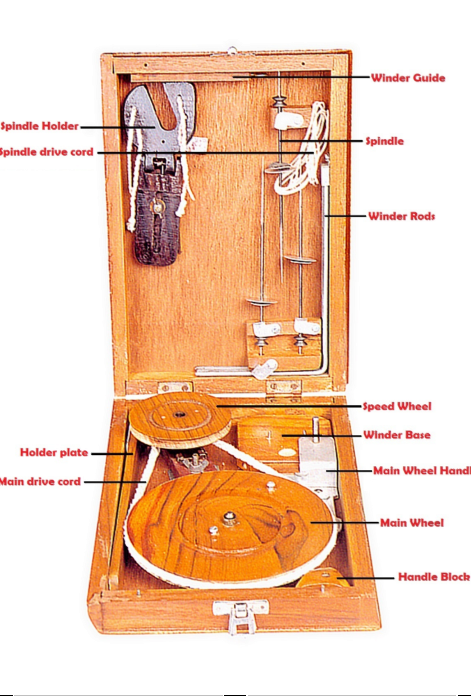

Type Of Charkha

Following model of charkha are used in present time:

For personal use:

1.Box Charkha

2. Traveler Charkha

3. Book Charkha

4 Ambar Charkha with two spindles

For professional use:

5. Ambar Charkha with 4, 6, 8 and 10 spindles operated both manually and solar

Learning The Charkha

When I started working in this organization, I participated in the morning prayer and watched others spin the charkha. They made it look so easy and simple. It fascinated me how effortlessly they do this. So intrigued I asked Muktaben if I could learn how to spin the charkha and whether she could provide me with one. She smiled and said that I should definitely learn, as it is a great opportunity.

The very next day, I was given a pati charkha—a portable version of the spinning wheel, designed by Mahatma Gandhi himself to make spinning more convenient during his travels. I was excited, but little did I know that learning the charkha was not going to be as easy as it looked.

A Journey

I have always been someone who learns best by doing. When I first saw a charkha, it seemed simple—I thought I just had to hold the cotton, rotate the main wheel, and the thread would come out. But it wasn’t as easy. You have to hold the cotton gently, spin the main wheel at the right moment, and maintain a specific speed. If you pull the cotton too strongly, the thread will break. If you rotate the wheel too much, no thread will form, and if you spin it too little, the thread will break. You have to find just the right balance.

When I first started spinning the charkha, the thread didn’t come out at all. And when it finally did, I spun the wheel too much, making the thread too tight, which stopped it from forming. Then, when I tried spinning the wheel less, the thread became too loose and kept breaking.

It was frustrating to see the thread break over and over again. I began to doubt myself, wondering if I lacked the patience to learn this skill. Everyone kept saying, “keep trying.” Frustration turned into sadness, but my determination to learn kept me going.

Slowly, I started to understand—how much to spin, how gently to pull the thread. I realized that you can’t overthink while spinning the charkha. You have to keep your mind calm. It feels like meditation, where you focus only on the movement of your hands and nothing else. My thread still breaks sometimes, and each time, I learn something new about why it happens. Sometimes, too much cotton gets stuck in the wheel because I place the broken thread beside it and sometimes I am holding the thread the wrong way.

Experiences

Once, while spinning the charkha and sitting near Muktaben for an hour, my thread kept breaking, and each time it broke, I became more frustrated. Seeing my frustration, Muktaben told me a story about Gandhi ji.

When Gandhi ji decided to shift the press from the city to the Sabarmati Ashram, no one was able to set up the printing machine. Everyone tried for several hours because they had to publish the magazine the next day, but to no avail. Gandhi ji asked everyone to go to sleep and take rest. The next day, when they tried with fresh minds, the machine started working. Muktaben then advised me to close the charkha and take some rest. The next day, with a fresh mind, the charkha ran smoothly.

“At first spinning charkha felt boring where the thread break every few seconds and you have to start again and now after month of practice its feel good in creating something from scratch.”

Manisha

“For first few days I just saw how others are doing it and when I first got my own charkha I started to ask several question why I was not able to make thLiread. And now that I have learned to make thread I think I should buy my own charkha.”

Niraj

Little kid here in the image is Pratik who is the trouble maker of our office. It was first time when he was holding the charkha.

Spinning The Charkha: Weaving Togetherness

Spinning charkha is more than a mechanical activity, It’s like meditation. You require patience, a calm mind and focus. Overthinking and frustration will only lead to more broken threads. And when you let your hand take control there is a smooth rhythm. Beyond individual experience, spinning charkha also fosters a sense of togetherness where we all sit together and try to learn something new and share the same difficulties. We share our experiences and stories.

The charkha was no longer just a tool for me; it became a source of meditation, a practice that required focus and presence. It taught me how to be in the moment, to not overthink, and to trust my hands to do the work. Spinning the charkha with my colleagues also fostered a sense of togetherness, making it a shared experience rather than an individual struggle. Through this simple yet profound act, we are not only keeping a tradition alive but also internalizing the very principles that Gandhiji advocated—self-reliance, patience, and perseverance. And in doing so, we are not just spinning thread; we are weaving a fabric of unity, mindfulness, and shared purpose.

0 Comments