When I first heard about the Sundarbans I thought to myself ‘Why do people live amidst so much uncertainty?’ In my calculation and world view, the idea of living on islands often struck by cyclones, surrounded by saline water, the fear of attack by a wild animal, and staying on land that might soon go down under really did not make any sense. This is the second part in an ongoing series to bring to you our learning from the fellowship’s travel workshop to the Sundarbans. The first part can be read here. And out of the many challenges the people here face, I have tried to put down three prominent ones that I witnessed in this piece.

The earliest mention of settlements can be traced back to 200-300 AD when a ruin of a city built by the Chaand Saudagar merchant community was found in the Baghmara Forest Block[1]. There are also mentions that in the Mughal era, Raja Basanta Rai and his nephew took refuge in the Sundarbans from the advancing armies of Emperor Akbar. The East India Company acquired the administration in Bengal in 1765 and in order to generate revenue they hired labourers from across the country to reclaim and cultivate the land. A round of migration happened in 1905, when a Scottish businessman, Daniel Hamilton bought three islands in the Gosaba block. He did so to prove to the British government that the cooperative (eutopian) way of life could work in rural India and a setup like the islands already cut off from mainland proved an ideal setting for his experimentation. Recent historical events of partition and the separation of Bangladesh have further pushed people to migrate to this region.

The struggle to separate fresh and saline water

“If you view the islands from the top, they will look like a saucer floating in the water. There is a fear of the islands getting sunk because of the rising water levels. Few islands are already sinking”

said one of the villagers

While the rivers flowing into the bay bring fresh water, the saltwater streaming up with the tide from the Indian Ocean makes the rivers saline (called nona jol meaning salty water in Bangla). With climate change, the salinity of the water is increasing. The extensive embankments in the Sundarbans called bundhs prevent the saline water from entering the cultivated field areas. They also hold back the daily high tides. These embankments are built on the perimeter of the island. But rising sea levels and frequent storms along with the poor quality of embankment construction have caused saline water to enter the island.

Once the water enters the rice field, which it did during Cyclone Aila and several other storms before it, the farmers cannot cultivate anything on that land for the next three years. The income thus generated by selling the rice gets wiped out.

For drinking purposes, there are wells dug. But due to the saline water entering the land, many sources of fresh water are contaminated by salt. When the saline water enters these ponds, there is a ‘gate’ – an indigenous technology in place which drains the pond’s fresh water into the bay. The people then wait for the ponds to fill up in the ensuing monsoon.

The frequent exposure and consumption of saline water cause severe health issues like uterine cancer, and blood pressure, especially in women. Few locals have turned this into a business opportunity and have installed water purifiers. Thus making the water safe for consumption but at a cost!

The vanishing land

“The place where you are sitting right now will be submerged in the water by 2024. We are building another place in the interior of the island. However, tourists demand to stay by the edge to ‘take in’ the beauty. So a resort inside is a step back”, said the owner of a resort in our interaction.

To know that the land beneath you will disappear in a year is not a usual thing. But people here have got used to it. In this case, the resort was on the riverfront and the owners will have to give their chunk of land for constructing new ring embankments to fortify the existing ones. A study says the ecologically fragile Sundarbans region in India and Bangladesh has lost 24.55% of mangroves (136.77 square km) due to erosion over the past three decades. Most of the erosion is permanent. Increased wave action due to storminess (natural) and reduction in sediments due to upstream dams (human-induced) are the two major drivers of permanent loss of land to water in the Sundarbans, researchers suggest.[2]

“This time it is my house, next time it will be someone else’s” say the villagers. When the river changes its course it enters the fields and destroys houses thus claiming back the land. This leaves people homeless overnight. Nature acts as an equalizer, never knowing whose fortunes will shift next. In most cases, people who are the poorest and belong to the lowest caste group live on the river’s edge.

We heard about the islands that have been submerged and the residents who had to migrate under distress. There were abandoned houses and community spaces – like a church that stood on the edge with its foundation exposed and waiting to be engulfed by the river, any time.

The looming fear of wild animals

Imagine this scene. You are sitting inside the house of a local, sipping chai and eating jhal muri (spiced up puffed rice). You are talking about their lives in general, trying to understand where their kids go to school, where the youngsters go for work, and what seasons they cultivate crops. You then see a shed built for their chicks and ducks, you admire how it is well-guarded with a roof. This structure is barely 50 meters from where you are sitting. And then suddenly the woman tells you that two years ago ‘he’ had attacked the chicken at night and taken away some. Hence the structure. The locals believe that it is an omen to call ‘him’ by ‘his’ name.

I froze, making an imaginary situation of what it must be like to see a tiger that close. From that moment, I no more wanted to spot a Royal Bengal Tiger in the trip.

Every year, thousands of tourists visit the Sundarbans national park with the hope to spot the royal bengal tiger. Very few ‘lucky ones’ spot it. Out of the 102 islands, 48 islands are reserved for forest. But like a lot of boundaries, this one too is not a physical one. The tigers can swim and move from one island to another. Accounts of an encounter with the bagh are numerous – some glorifying how the villagers killed the tiger and somewhere the tiger carried away the people who went to the forest. The locals have a philosophical way of looking at this co-existence. They say,

“If the tiger enters our territory, we kill it. When we enter his, he does the same.”

The source of livelihood for most of the locals requires them to enter the forest. Occupations like fishing, crab hunting, prawn seed collection, beekeeping, and wood collection are followed by the people here. These require people to venture out into the forest or into the river. Often, they dock their boats on shallow waters and get down, knee deep into the mud and get busy sieving through the half mud half water. During such visits, there is a fear of attack by crocodiles and tigers – a lucrative and easy spot for them really to attack and drag the human body back into the depth of the sea or forest respectively.

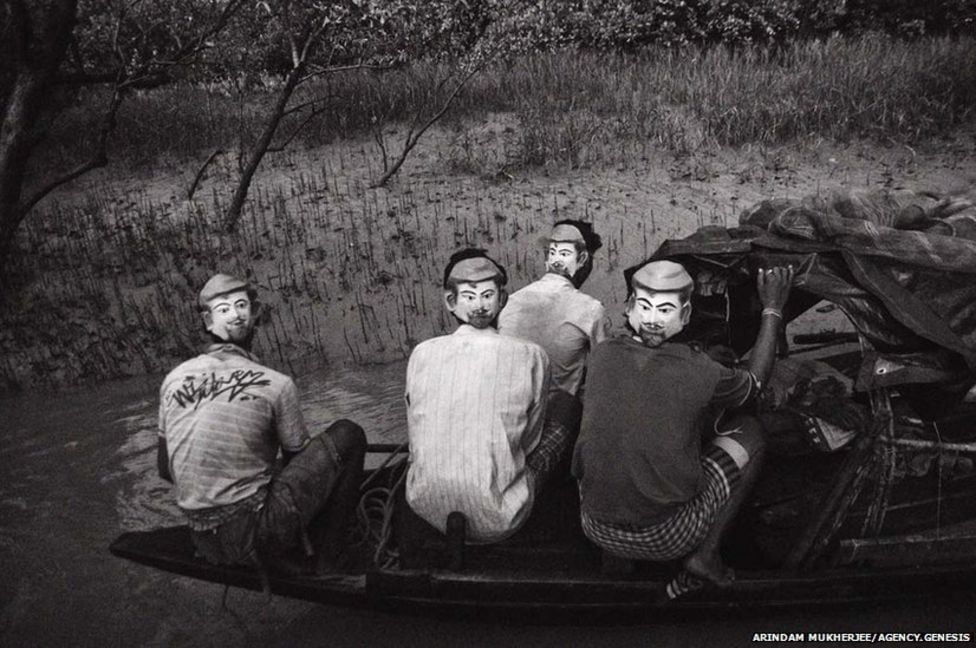

Since the formation of the reserve in 1973, the forest department has tried ways for humans and tigers to co-exist. Fences have been wired around the reserve islands hoping to prevent the predator from crossing over. Face masks have been distributed for people to wear on the back of their heads with a belief that the predator only attacks from behind. In spite of all this, the attacks haven’t stopped. The numbers quoted by the locals and those released by the forest department are not even close. There is a long-standing battle with the forest department for compensation and regulations where the locals are losing, both their lives and livelihood.

References:

[1] Recognizing and Rewarding Best Practices in Management of World Heritage Properties

[2] A Cloud Computing-based Approach to Mapping Mangrove Erosion and Progradation

0 Comments