In March last year (2019), the Supreme Court put aside its own 2009 judgment and set six convicts free, who were earlier on a death row. It was a first-of-its-kind ruling. They were convicted by multiple courts, including the Apex, in a r*pe (and multiple murders) case in Nashik. It was eventually ruled that the six men were falsely implicated by the police. All of them, who spent 16 years in jail for a crime they never committed, belonged to the nomadic tribes formerly declared as “Born criminals”.

De-notified Tribes (DNTs) are those communities which were notified as ‘criminal’ under the British colonial Criminal Tribes Act, 1871. After almost a century of horrors as a result of this discriminatory law, they were de-notified by the government of independent India on August 31, 1952. Criminal Tribes Act was repealed only to be replaced by the Habitual Offenders Act (applicable now to individuals, and not entire cultural groups). Stigma persists.

DNTs continue to be denied access to housing, healthcare, nutrition, education, livelihood, political representation, justice and lives of dignity. It’s scary how little we know/are taught about this history, the effects of which insidiously sustain themselves in the current Brahmanical-bourgeois paradigm.

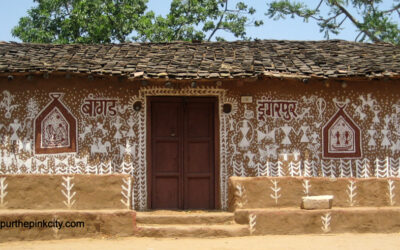

The Baori Basti in Sawai Madhopur, occupied by DNTs, is marked by dilapidated make-shift shanties, muddy kachcha roads and no facilities for waste disposal. Upon discussion with the community leader, an elderly woman, with a face wrinkled with tiresome perseverance, it is clear that their persisting issues include water scarcity, constant tiffs with officials while receiving ration, unsanitary conditions – exacerbated when the rains cause water-logging and overflowing sewage, unsteady income, lack of access to education and healthcare, helplessness during medical emergencies, malnutrition and alcoholism.

Despite being considered a crucial vote-bank by political aspirants, and the community’s needs especially those of another water tank and pakka roads being regularly articulated to the authorities, the necessary work is yet to be done.

Their primary source of income is selling hand-made decorative items/show-pieces, for which they acquire material (glass, plastic and paper) from Delhi. Collectively, items worth Rs. 5000-6000 are bought, put together by hand and the final products are sold either separately (miniature mandirs), or in sets of 2 and 4 (varieties of potted paper and plastic flowers) for Rs. 100-150, in Sawai Madhopur and nearby villages. Sale, however, experiences seasonal fluctuations, surging during festivities and negligible for the rest of the year.

Additionally, due to the pandemic, the journey to Delhi has been hindered. This is especially because they struggle to save enough for tickets and tend to travel without them, which is impossible now given the strict regulation of movement. Competition from cheaper, ‘better’ quality factory manufactured products compounds their problems.

For daily income, multiple members from a household, often including children, leave at the crack of dawn to collect scrap and garbage, which they then sort into different categories such as cardboard, plastic, metal and electronics, to be sold to the kabadi-wala. Their income per kilogram currently ranges from Rs. 2-3 to Rs. 5-7, depending on the material. This is subject to change, based on the day’s collection of the kabadi-wala. Due to the lock-down and other pandemic-induced deterrents, rag-picking has also taken a hit, especially with the nearby hotels, usually a major source of plastic trash, being closed or largely unoccupied.

Gramin Shiksha Kendra (GSK) is seeking to provide the children at the basti a structured learning environment through daily sessions, in an attempt to ease them into eventual enrolment to teaching, playing and socialising set-ups at nearby government schools. Apart from supporting these first-generation learners, using its usual child-centric and multi-grade/multi-level approach, the organization is also helping the Baori community in getting the Aadhaar card, Pension card and Voter ID card made. Additionally, they also constructively communicate with local leadership to enable access to welfare schemes. A research study is being done to understand the value of supply chains that the community members are a part of, so as to develop suitable livelihood-oriented interventions.

Study sessions are held every morning at the revered Hanuman Mandir, the only space in the basti that can accommodate this exercise

Residents of the Baori Basti in conversation with MLA Danish Abrar, discussing their issues and needs

While cooking for her husband (who is out selling hand-made decoratives) and four children, she tells me about her livelihood and the struggles of running the household

Why did I provide this oddly specific account of the daily lives and struggles of some 125 families residing in this one basti? It is because our developmental discourse is often exclusionary, and glosses over its own failure to accommodate the narratives of the most vulnerable and ‘invisiblised’.

For a Political Science student like me, who received quality schooling and can access all that the internet has to offer, it should not have taken working at Gramin Shiksha Kendra at the age of 21 to hear about DNTs. This is my humble attempt to spread the word. May we all do the task of amplifying marginalized voices, and ensuring that they pierce through the cluttered bombardment of all the information and literature that we constantly consume.

0 Comments