Two Days. Two Life Stories. One Thread of Courage.

Recently, I had moments that left me awestruck not once, but twice. Two days. Two life stories. And yet, one common thread. Let me rewind a bit.

As part of the EarthJust team, I visited the Justicemakers Mela, organised by the Agami in Jaipur, Rajasthan. The space was alive with colour, conversation, curiosity, and courage. It was designed for stories to flow freely: of justice and law, woven through panels, baithaks, art, music, play, and theatre. Stories that did not sit neatly inside frameworks, but spilt into lived experience. And it was here that I encountered not one, but two stories that stayed with me long after the mela ended.

A Story That Was Never Told Before

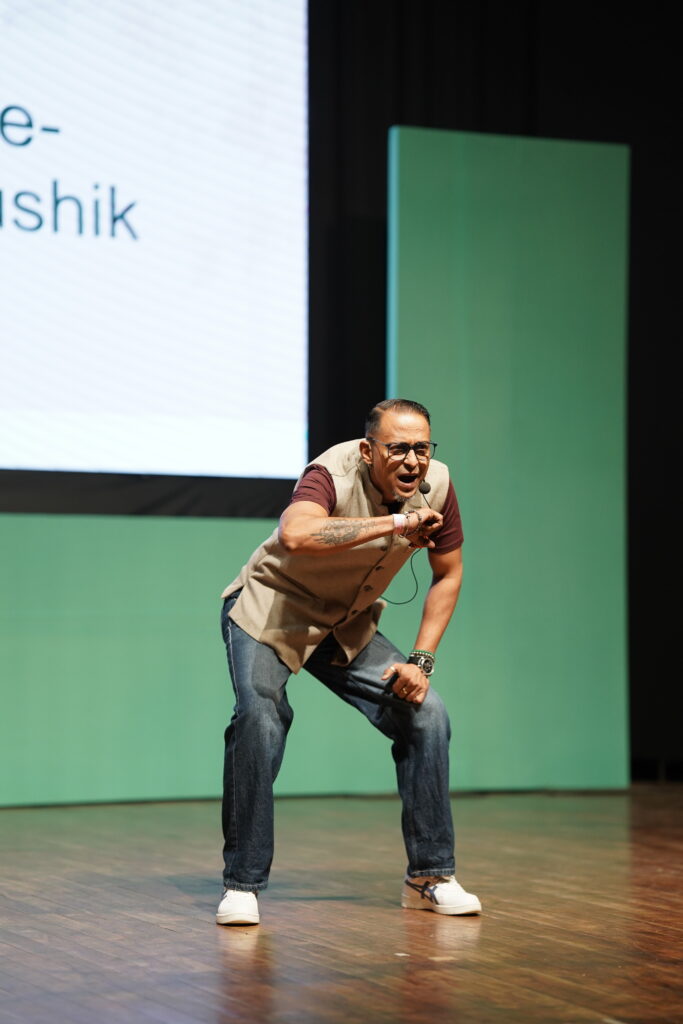

A tall, lean man, I would guess in his late forties, walked onto the stage. Behind him, the screen read second life. At that moment, I was completely clueless about what was about to unfold. With a slight American accent, Shailendra began narrating his journey.

He had gone to the US to pursue his bachelor’s degree, carrying with him the aspirations of a middle-class Indian household and the quiet hope of making his family proud. But fate, as it often does, had other plans.

One night, after university, he was out with friends. Drunk. Carefree. What began as an argument with a friend over a financial matter spiralled into something irreversible. In a moment of impulse, Shailendra killed his friend.

Trying to navigate an unfamiliar legal system in a foreign land, with not much financial aid, he reached out to a public defender, believing this person would help him. Instead, he fell prey to racism. Despite knowing the full context of the situation, the public defender repeatedly told him he would face a twenty five year sentence. Young, scared, and alone, Shailendra had no option but to believe his so-called defender.

Then came the courtroom.

The judge examined the documents, listened to Shailendra’s account, and did something unexpected. He threw the papers in the air. He flagged serious issues in the case and revised the sentence to fifteen years instead. It was a moment of shock. On one hand, Shailendra was deeply disappointed. On the other hand, he felt an immense sense of relief.

Jail, as he described, was no cinematic exaggeration. The US prison system was brutal. The prison was overrun by gangs. The place felt dark, both in its walls and in its people. There was no natural light, only harsh voices and hardened faces. Violence was constant, crime was routine, and fear was always present, especially the fear of sexual assault. It felt less like a prison and more like a hellhole. For the first six years, frustration, loneliness, and helplessness consumed him. He lashed out, injuring other inmates, doing whatever it took to survive.

Until one day, sitting alone in his cell, something shifted. He began to reflect, replaying every decision, every moment that had led him there. And in that reflection came guilt. But this time, guilt did not destroy him. It became the seed of a new chapter.

Shailendra started reading. Working out. Keeping to himself. While reflecting during those long hours in his cell, Shailendra also wrote a six-page apology to the victim’s family. A letter filled with remorse, accountability, and grief. There was no response. He did not expect one. He knew that no apology, no matter how sincere, could ever bring their son back. Writing that letter was not about closure or forgiveness. It was about acknowledging the weight of what he had done and learning to live with it honestly.

His only goal became simple and primal: to get out alive. Ironically, the violent reputation he had built earlier now protected him. People rarely messed with him. What terrified him most was not the jail itself, but the possibility of never leaving it and never seeing his family again. Of life simply ending there

After years of discipline, patience, and sheer will, he was finally released.

Friends helped him return to India. One of them insisted he download Tinder, a suggestion that felt absurd at the time, but ended up changing everything. Within days, he met the woman who would become the love of his life. They got married. And slowly, Shailendra began building his second life.

With no degree and no CV, he struggled to find work. His savings ran out, and he eventually began working as a cab driver. Ironically, the survival skills he had learned in prison made him exceptionally good at it. He could sense a passenger’s mood, respond intuitively, and adapt instantly. His ratings soared. He drove people to hospitals in emergencies. Saved lives by reaching the right place at the right time. During COVID, he went far beyond his call of duty. Every time he dropped someone at a hospital, his wife would say, “Roz jung par jaate ho,” you go to war every day.

Years later, he and his wife started a small brand that eventually flourished on Amazon.

As his story ended, the auditorium fell silent. Teary-eyed, the audience rose for a standing ovation. Shailendra walked off the stage and hugged his wife. Most people had already left, but a few stayed back, not for selfies or autographs, but to quietly witness the tenderness between him, his wife, and their children.

What surprised me most was the precision with which he narrated his journey. I assumed he must have told it hundreds of times before. This was his first time. And while I was emotional listening to his life story, what truly moved me was his courage. The courage to share it for the first time, in front of strangers, and in front of his eight-year-old daughter. I stood there, watching a man who had just laid bare his most vulnerable self.

Another Story, Waiting To Be Heard

After the second day of the mela, we returned to our Airbnb. As we entered, someone else walked in too. Knowing he was a friend of my mentor, I offered to help with his bags. He politely refused, but I noticed something unusual about his thumb. Questions flooded my mind, so much so that I forgot to even greet him.

This was Anurag, a friend of my mentor, Shruti from EarthJust. He had just returned from Hong Kong and had missed the mela. Since we were in his hometown, he decided to visit. It was past midnight. We were exhausted, half asleep, and had an early morning train to catch. And then Shruti said, “tum sabko Anurag ki filmy story sunni chahiye.” It was like a drumroll to our ears.

Anurag began casually. Engineering, Teach for India fellowship, working with startups, building entrepreneurship and impact ecosystems. I remember thinking, Is this really worth losing sleep over? Then he said, “On 17th April, 2023, when I was climbing my eleventh mountain and my first 8000 metres mountain, Mount Annapurna (8,091m), in Nepal. I was crossing one of the most dangerous sections between camp 3 and camp 2, an area highly prone to avalanches. Due to a rope failure, I mistakenly picked the wrong rope; that rope should not have been there …”

He continued, “I had a catastrophic fall at ~6000m and then entered into a deep, icy crevasse, 70m under the Earth. I was alone and completely helpless. The place was so isolated that no one could hear me, see me, or even know where I was. With temperatures lower than minus 30 degrees celsius, I had no food, no water, and barely any oxygen. I lay there for three days and three nights. It wasn’t the ice or the cold that scared me the most. It was the fear and the loneliness.”

Anurag spoke about Mount Annapurna and its reputation. Known for its deadliness, it takes the life of at least one out of every three climbers who attempt it. A close friend of his, a ten-time Everest summiteer, had also lost his life there in the same year. His chances of survival were almost nonexistent. Hope, he said, was his only companion. The belief that Maa Annapurna would not let anything happen to him.

Back home, his family, friends and thousands of well-wishers were doing everything they could. They reached out to government ministries, senior officials, and top CEOs. No option was left unexplored. But on the ground, reality was harsh. The local sherpas had little hope and limited ability to attempt such a risky rescue. Then, almost by chance, two Polish climbers who were there along with a team of Nepali sherpas and a helicopter pilot voluntarily decided to recover his body on the fourth day.

When one of the Polish rescuers reached the bottom of the crevasse, he found Anurag ALIVE, fully covered under the snow and ice. He was pulled out, but survival alone was not enough. He needed immediate medical care. The next challenge was airlifting him. A helicopter pilot lifted him out of the mountains and flew him to the nearest hospital in Pokhara.

At the hospital, Anurag was declared dead after the first 30 minutes of CPR. His family, especially his brother, refused to accept it. His brother pleaded and argued with the emergency doctor. What followed was four hours of continuous CPR. Against all odds, Anurag finally took his first breath again. I was stunned. My mind struggled to comprehend what modern medicine, or perhaps something beyond it, had made possible.

Anurag survived, but his body was in critical condition. Severe cold burns, multiple internal injuries, and a real possibility of permanent brain damage. Strangely, there were no fractures. Over the next seven months, he underwent seven surgeries and countless therapies. His body had lost all muscle memory. His right-hand thumb and left foot toe were amputated. Half of his skin was grafted. He had no conscious memory of the incident.

Suddenly, my unanswered question made sense. When I asked him what he remembered last, he said quietly, “I don’t remember recording a video. But I did record myself during those three days. The night before I was rescued, an avalanche buried me. Before my GoPro died, I said goodbye to my friends and family. When I saw that video later, I couldn’t stop crying.” Anurag returned to life as a 34-year-old child. He had to relearn the simplest things, how to smile, eat, walk, and even use the toilet.

“I have seen the mountain, and the mountains have seen me,” he said.

But his story did not end with survival. Instead of blaming the weather, the mountain, or fate, Anurag redirected his entire energy towards protecting glaciers. Maa Annapurna saved me, he said. How can I turn my back on her now? I struggled with this. How could there be no anger? No resentment? While I focused on the half-empty glass, Anurag simply said, “I could have been dead. But she gave me another life. Glaciers are like our grandparents. They took care of us first. Now it is our responsibility to take care of them.”

I had never looked at glaciers that way. Forests, animals, rivers, yes. But glaciers?

“If we can protect Ganga, why can’t we protect Gaumukh glacier?”

That question stayed with me.

Anurag felt like a living example of a miracle. But what stayed with me even more than his survival was his courage, his resilience, and his quiet optimism. I was deeply moved by the way he chose not to grieve endlessly over what had happened to him. Instead of sobbing over his tragedy, he transformed it into a life mission. There was strength in that choice, and a rare kind of grace in how he carried it.

With that gratitude and responsibility, he has started to build The Voice of Glaciers Foundation, an ecosystem for glacier risk, uniting science, data, storytelling, and policy to prepare mountain communities for glacial loss with dignity, agency, and resilience.

Anurag, after the incident, fully recovered, on a field visit to Drang Drung Glacier in Ladakh, India.

Credit: Anurag Maloo

What These Stories Left Behind

These stories may or may not be Bollywood material. But they certainly broke my brain’s box office. I am amazed by the courage of the narrators. What made both journeys deeply human was the fact that neither of them shied away from vulnerability. Neither story villainised anyone. Neither sought sympathy. They simply offered truth. They chose to share their most fragile moments with people they barely knew, and in doing so, reminded me how courage often looks quiet, honest, and open.

I kept thinking about how powerful the human mind is, how it can keep us stuck or help us move forward. What stayed with me was how both narrators chose progress over collapse. Not because their situations were easy, but because they worked with their minds every day, choosing reflection and responsibility over giving up. Perhaps it is important to sit with both our mistakes and our strengths at least once in our lifetime, to understand what we are capable of and how much choice we hold in shaping what comes next.

When I step back, I see how both these stories are quietly linked by the same thread that first appeared on that stage in Jaipur – a second life. For Shailendra, a second life came after guilt, accountability, and survival. For Anurag, a second life came after fear, resilience and rebirth. My thoughts also went to their families. To Shailendra’s family and friends, who stood by him through his lowest moments. To Anurag’s family, who refused to give up even when they were told he was no more. It led me to a quiet realisation that in situations as grave as these, a steady mind, courage, and a strong support system are not luxuries. They are what make survival, healing, and moving forward possible. Both stories filled me with hope.

“Hope that each of us will shine in our own story, if not in someone else’s. That confronting guilt and fear can open the door to beautiful second chances. Hope that eventually things work out.”

0 Comments