In rural India, addressing health and nutrition challenges remains a critical issue, particularly among pregnant women (PW). Among the most concerning issues are anemia and inadequate maternal health services, which significantly affect both maternal and child health outcomes. Despite the presence of government health initiatives, gaps persist in rural communities where awareness and involvement in monitoring maternal health and nutrition remain limited. This lack of awareness becomes even more concerning when there is insufficient engagement from local leaders and community members, which weakens accountability and slows progress in improving health outcomes.

Bahraich, our program area, faces systemic barriers in tracking and addressing health concerns, including anemia in pregnant women and malnutrition in children. The nutritional burden is staggering, with 64.38% of children suffering from anemia, 52.11% being stunted, 14.35% wasted, 7.47% severely wasted, and 38.04% underweight, out of a total of 545,796 children.

Given these statistics, it is crucial to engage all stakeholders in the discussion and solutions. Local leaders often lack access to real-time health data, engagement with the frontline workers and sometimes even alienate maternal health concerns as “women’s issues” making it difficult to identify gaps in health services or respond effectively to challenges faced by frontline workers at the village administration level. As a result, there is limited local ownership of health issues, and accountability mechanisms are weak.

The Poshan Prerna program, where I am currently placed in, recognized the need to address these challenges by empowering communities with transparent, accessible health and service data. By creating a tool for community-based monitoring, the program aimed to bridge the gap between frontline health services and community-level accountability. This initiative sought to ensure that maternal health data, particularly related to anemia, was not only collected but also made visible to the community and local leaders, with the aim of instilling a sense of shared responsibility and action.

Intervention: The Nigrani Toolkit

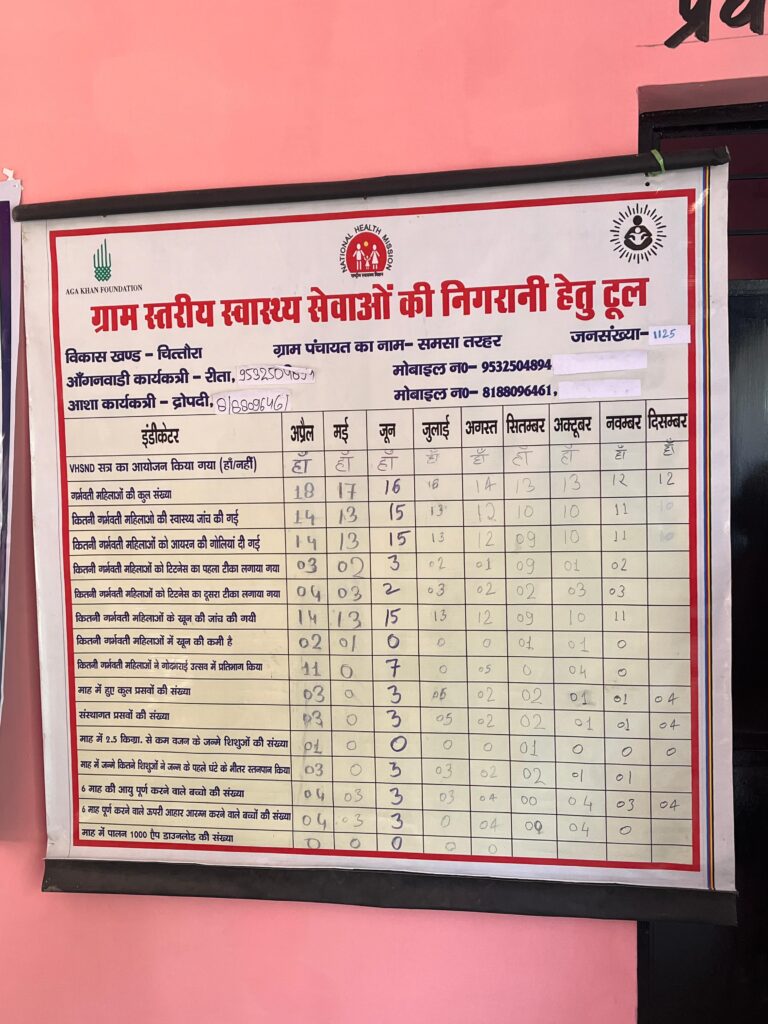

The Gram Stariya Swasth Sevaon ki Nigrani Hetu Tool, also known as the Nigrani Toolkit, is a community-based monitoring system developed to track key maternal health indicators and foster collective accountability. Now functional in eleven Gram Panchayats and soon to be scaled up to twenty, the toolkit is a chart-based system that tracks monthly health and nutrition on sixteen indicators, with a primary focus on pregnant women and their antenatal care. Some themes the key data points record include:

– Number of pregnant women receiving antenatal care (ANC)

– Number of pregnant women receiving iron and folic acid (IFA) supplementation

– Instances of anemia among pregnant women

– Uptake of TT (Tetanus Toxoid) vaccinations

– Other essential maternal health indicators

This systematic tracking ensures that vital health data is captured and shared in a transparent manner. The chart-based toolkit is filled collaboratively by frontline health workers during the Village Health, Sanitation, and Nutrition Day (VHSND) sessions. ASHA workers, Anganwadi Workers (AWW), and Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (ANM) play an active role in documenting these indicators and help us ensure that the data collected is accurate and reflects what is happening in the village.

Once the chart is completed, it is displayed on the walls of the Anganwadi Center (AWC) to create a visible and constant reminder to the community of the progress made, the gaps that remain, and the collective responsibility to improve maternal health. The chart provides a snapshot of local health indicators that are accessible to anyone visiting or passing by the AWC, including community members and government officials.

Engaging Village Leaders For Accountability

To enhance the effectiveness of the Nigrani Toolkit, the programme realised that it is essential to engage local leaders and instil a culture of accountability within the community. This is achieved through monthly PRI Baithaks (meetings), where local leaders, PRI members, and influential community figures come together to review the data captured in the Nigrani Toolkit.

These meetings become a platform for discussing key health issues, including the anemia rates among pregnant women, the uptake of IFA pills, and if the frontline workers are facing any infrastructural, institutional or community based problems. The data displayed on the chart acts as a conversation starter, allowing attendees to identify areas that require attention and take action accordingly. This platform ensures that health outcomes are not solely the responsibility of health workers but are shared by the entire community.

The PRI Baithaks also provide an opportunity for frontline workers to report on their efforts, challenges, and successes. They can discuss the barriers they face in implementing health interventions, such as if there are vaccine hesitant families (known as Inkaar Parivaar), they may employ the help of influential villagers or political leaders to help convince them. In turn, community leaders and PRI members can offer support, provide funds for resources from the VHSNC fund, and collaborate on solutions to ensure services for the community remain hurdle-free.

This participatory approach promotes sustainable change, as it encourages the community to take an active role in addressing health challenges.

Impact

The Nigrani Toolkit has shown significant promise in enhancing transparency and accountability in rural health services. By making health data visible to the community, it fosters a sense of collective responsibility, empowering local leaders to make informed decisions and frontline workers to better reach their beneficiaries.

Although the responsibility for filling out the data ultimately lies with the person being held accountable for their services within the PRI, frontline workers understand that the process is not intended to implicate them but rather to ensure that they can effectively serve the entire community. As ANM Suman from Chittaura shares,

“Initially, I faced difficulties in measuring the haemoglobin (HB) levels of beneficiaries because my HB meter wasn’t working. I raised this concern during the PRI meeting, and the Pradhan acknowledged that ANC checks were being compromised. As a result, some funds were allocated for repairs and to purchase a new device. Now, HB is tested in every VHSND session, and the new devices give accurate readings.”

In Balha, a different challenge emerged during a PRI meeting. It was observed that although weekly iron and folic acid (IFA) tablets were being distributed to children at the Composite School, about 80% of the children discarded the tablets. When the children told their parents about the “unknown medicines” they were given at school, parents voiced concerns to the teachers and requested that the tablets no longer be given. After a few incidents, the distribution of IFA tablets was halted.

However, the active participation of Panchayat members in the discussions led to a solution. They identified the gaps and worked with service providers to implement corrective actions. Now, every Monday, children receive IFA tablets, and it is ensured that all students take them. For those who miss school on Monday, a teacher is assigned to give them the tablet on Tuesday. Additionally, a Panchayat representative voluntarily visits the school every Monday to ensure the children take their IFA tablets under supervision.

Future Directions

The success of the Nigrani Toolkit demonstrates its potential to be replicated in other rural communities, expanding its impact beyond the current implementation areas. By incorporating additional health indicators and increasing community involvement, the toolkit can serve as a model for other health interventions focused on improving maternal and child health across rural India.

Looking ahead, future efforts will focus on refining the toolkit to include more maternal and child health data points, integrating it further with existing health systems, and scaling the intervention to reach more Gram Panchayats. Ongoing evaluation will be essential to identifying areas for improvement, ensuring that the Nigrani Toolkit continues to be a valuable tool for community-based health monitoring.

0 Comments